On Writing in English

My relationship with English began with the need to forsake my origin, to renounce my identity.

Born in Indonesia, I was raised to be bilingual, speaking both Javanese and Bahasa Indonesia simultaneously: the former being my mother tongue, the latter the tongue that united my nation.

When I first began to read, I read only in Bahasa. Despite its integral function in my life, Javanese felt, and still feels, elusive. My grasp of it is rudimentary, even more so now with the language receding in relevance. In contemporary Java, no one writes in the original Javanese script anymore. We resort, instead, to the alphabet, to spelling words as they sound to the ears, to coining new ones along the way, making the language seem crude and structureless, arbitrary and provisional.

Bahasa, on the other hand, seems richer and more capable on the page. It is contained and systematic. Javanese, my mother says, is to speak and feel in. Bahasa is the language of debate and discourse, and what governs my interpretations of texts and theories. When I read my books in kindergarten, I liked to trace the sentences across the page with my finger, hoarding new words to decipher and memorize, to later use in my journal.

Despite our budding love, I refused oftentimes to speak Bahasa beyond what was required of me. I have a Javanese accent and I do not sound like people from the capital city, to whom Bahasa is ubiquitous. As a child, I used to accuse my accent of tainting my speech, of hampering my eloquence. When spoken, Bahasa feels foreign, as if denying me access. I belong to the language only on the page, in its written form. To communicate, to jest and to express my anger, I rely on Javanese.

When I began to write stories, I did so only in Bahasa. My stories were short at first, a page or two. Then gradually the plots grew richer, warranting longer narratives. Once finished, the stories would sit in my journal for weeks, undisturbed and unedited. The characters would at times demand revisiting, but I never saw the perks of sharing them, though one day I resolved to submit one of them for a class project, for which my Bahasa teacher showered me with compliments. She pronounced mine the best in the class and showed it to another Bahasa teacher, who, later that year, sent me to my first writing competition.

Throughout my early adolescence, I maintained this habit: writing in Bahasa while speaking largely in Javanese. My environment, too, helped me reify this habit so that there was a physical barrier: at school, Bahasa reigned; at home, it was trampled down by Javanese. The wall was not completely impenetrable but it was still there, like a thin screen of mist.

Once I moved into a boarding house for high school, a third language arrived to tip that linguistic balance. English, which used to be a mere subject I had to study for, a test I had to pass, suddenly assumed a growing significance in my life. In my semi-international school, it was everywhere, constantly engulfing me. It invaded my books and class presentations; it demanded an eight-hour relationship five days a week. My learning was done fully in this language. Knowledge seemed valuable only when transferred through the medium of English. In the first month of school, I grappled with words again like a child, translating terms, converting them as I would foreign currencies.

Because it was the key to my academic success, because mastering it was now vital, English became the subject I would study the most after school. I wanted to excel at it; I wanted to make no mistakes. Once a month, I would loan a TOEFL prep book from the library and do some exercises. On weekends, I would watch a series of American movies and learn new phrases, pretending, at times, to be an American boy sitting in a classroom, answering difficult questions in impeccable English.

Albeit pervasive, the language never interfered with my writing. I continued producing stories in Bahasa, sending them to contests, emerging as the first-prize winner. At a certain point, my short story was anthologized. The book arrived in the mail within a week after the announcement, and I kept it underneath my bed, within reach. My last name was misspelled, but my sentences were kept clean, preserved, uncontaminated. Although I doubted anyone read the book, it was still my biggest accomplishment, proof that my Bahasa, my grasp of the language, had not failed me.

With accomplishments and praise comes criticism. A judge from a writing contest I had participated in, a man in his forties, told me his opinion on my story. The piece retails the journey of a schoolboy who defies his Divinity teacher’s demand, and refuses to accept gender inequality prescribed in the Quran. The judge, having analyzed my story, said that my worldview was too pessimistic. He questioned my faith in God. At great length, he lectured me about the responsibility of a writer and their duty to promote change,telling stories that guide people to the right path, not otherwise.

At the time, I did not object to his principle. Instead, I, too, began questioning my own writing, realizing its impact on other people. I abandoned my pen and paper for a while, not out of despair or a grudge, but because I was overwhelmed by the burden of being a writer. I did not know if I was a writer or if I wanted to be one. I loved writing, and there was that. I never intended to ensnare other people in my fantasy world.

To distract myself, I devoted my time to school, to study Biology and learn English. By the end of my first year, I had taken my GCSE exams, won a debating championship, and become the Editor in Chief of the school newsletter. I accomplished all of that in English. The language became my vessel for achievements, and I increasingly depended upon it. When I applied for and later got a scholarship to study in the Netherlands, at once I severed all ties with Bahasa and Javanese. I had to live in English now, dream in it, and survive with it. There was no way around it: I had to immerse myself in the language and the world it represented.

For once, I was never leery of English’s dominating influence on my life. There was never a question of anti-nationalism or submission to the West. It was a matter of survival, of advancing my career. I needed the language, and the language seemed to embrace me. In my head, I was granted no other options.

But that isn’t necessarily true. I myself chose to apply for the scholarships. I chose to study abroad. I was the one who oriented my path so that English could make its way towards me. I wanted the language, and the language did not reject me. With each day the fact became more clear and irrefutable. After I dropped my Indonesian literature course and substituted it with an English one, from then on, I knew I was guilty of preferring the English language, of desiring its full embrace. From then on, I knew I was headed west.

Given this change, I stopped writing stories altogether. In the two years that I was abroad, my Javanese and Bahasa suffered immensely. I lost authority over my mother tongues, while at the same time, was kept at bay by the English language. I was getting better at speaking English, but my accent would impede my flow. I would read books in English but concurrently echo the sentences in Bahasa. I would tell a joke that in Javanese sounds funny, and nobody would laugh.

Incapable of originality, I resorted to emulation. I mimicked my native English-speaking friends and their accents. I consulted the internet for every sentence I typed on the computer. I resented handwriting exams because I could not make errors or scratch my sentences too often. I metamorphosed, in an instant, into a sponge, absorbing information and new phrases every minute, producing something only when demanded.

Even after my English literature teacher told me he wanted to grant me a high predicted score, I was still suspicious of my abilities. Almost immediately, I refused his offer on the grounds that it was too drastic a change from the previous year, in which I was quite possibly the worst student in the class. His kindness and enthusiasm flattered me, but I did not deserve it. I was not yet as fluent in English as I would have liked to be. I spoke three broken languages.

For years, from high school and all through my freshman year of college, I deprived myself of the joy of storytelling. By then, writing in Bahasa was no longer possible. I had forgotten most of the words, and my sentences sounded forced. Doing it in Javanese was not possible either: it was never in the picture to begin with. All I had was English, and how could I possibly write a story in a language I did not belong to, when my command of the language was far from perfect?

The question startled me. I remember asking: but who has the perfect command of the English language, anyway? Who does the language belong to? The language has been dubbed a lingua franca, and it has permeated almost every culture, transcending countless borders. No one owns the language; anyone can access it.

Almost spontaneously, I began to read fiction again, more voraciously this time. Proust, Baudelaire, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Tolstoy — I read translated works by international writers who, without English, managed to change the world. I began to read works by English-speaking writers whose fantasy worlds were accented and unique: Jhumpa Lahiri, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Mavis Gallant, Andre Aciman, Indra Sinha. They reminded me that English is a no man’s land and I was summoned back to the world of writing.

In October 2017, I remember I wrote the first draft of my first short story in English. It is based on a true event, about a soldier who encounters a pregnant woman in a wartorn Medan in Indonesia. The process of writing it was exhilarating. I had to sit with this obscure portrait of somebody’s life in my head and intuit its meaning, a process akin to reasoning with chaos. I remember the joy of seeing the document and the many hours I subsequently spent on revising it. Since then, I have written many stories, none yet published. They sit in my journal like they used to, constantly revisited, waiting to see the light of day.

All fiction writers, as David F. Wallace once described, tend to be oglers. They lurk and stare, lurk and stare, trying to invent ways to give life a form and structure. Their nature as watchers, studying others from afar, necessitates the call for a reasonable distance: to remain invisible and yet incredibly present, to be able to retreat into a watchtower and survey the crowd below.

Writing in English, my third language, has allowed me the illusion of exile, a state of perpetual estrangement and anonymity. The language detaches me from the reality in which my stories are rooted. It is, in a sense, my watchtower.

When I am abroad, I am a foreigner, writing about a new reality, a new society, as an outsider looking in. When I am back home, writing about my people, I think in another man’s language so that even when my surroundings seem familiar, and the reality supposedly mine, I still feel reasonably distanced from it.

For a class project, I submitted the piece I wrote about the soldier and the pregnant woman to my college professor. I sat with her one day and she told me about how she appreciated the rawness of the protagonist’s character: an agnostic man struggling with the moral implications of killing enemies in the name of war. And when I was with her, I thought about the judge from my writing competition, what he would have said about my story had I written it in Bahasa. Would he think it defiant of Islamic values? Would he, again, question my faith in God?

Because English, in this globalized world, is a part of this interconnected network of cultures, it belongs to all and none of them. The language is not bound to a specific set of norms or values; it is free. In English, I too feel stateless, like a non-national. In English, I am a spectator, an onlooker. In English, above everything else, I am proud to call myself a writer.

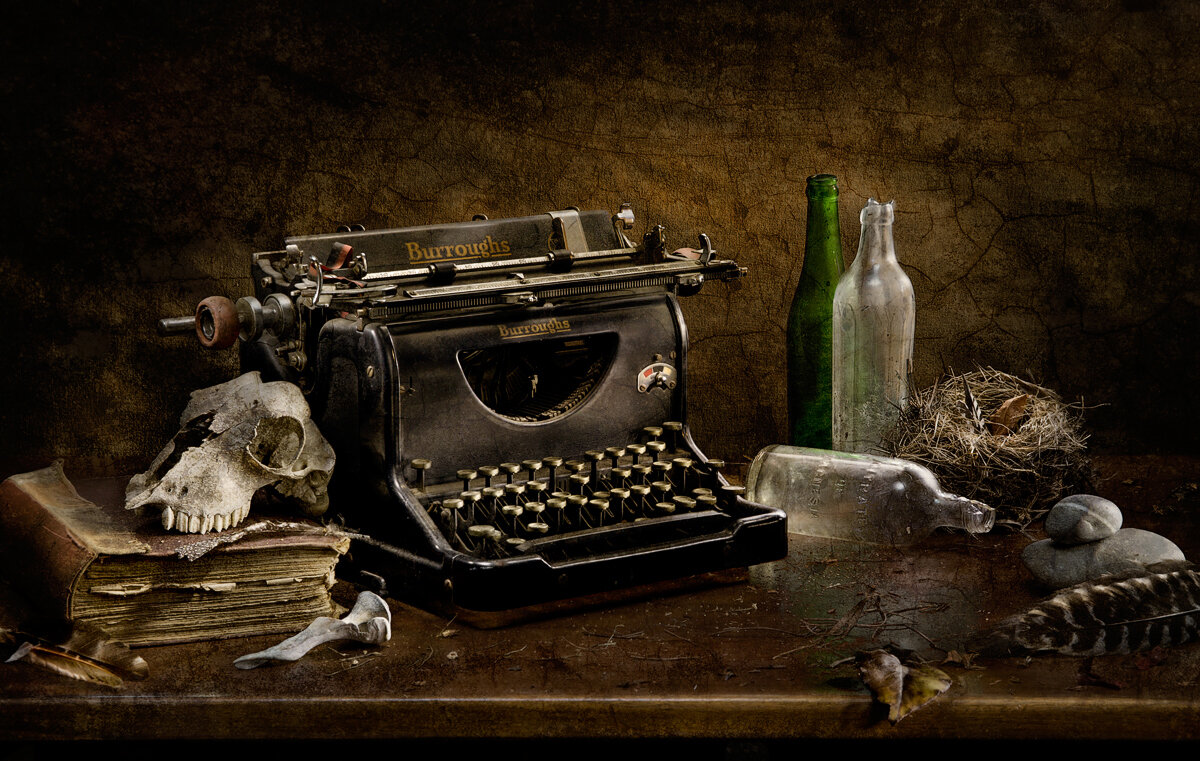

Artwork by Kathy Buckalew