Ladies in Waiting

Every morning the wives, sisters, and daughters gathered at the dock to look for the men who had gone. The women came dressed in dresses. Most of the dresses were a soothing blue with white collars. The women sometimes carried embroidered handkerchiefs. They’d pat at their dry eyes from time to time with the coarse fabric. The women waited honorably, stiff-backed and high-chinned, hair knotted elaborately to hold it in place. The biting winds bloomed rosy cheeks and their hands were folded over chests or wrapped around necks with wrists forward or in a covered fist at their stomachs. The waves frothed white as milk. The moon was stillborn in the sky to the left. The ocean was empty as ever.

After three hours of glaring into the sea, they broke ranks. Emptying into the streets, eyes blurry from the shining sea, they went home to sweep or tidy or prepare a meal. While they completed these tasks, they waited. After the tasks were completed, they waited. As they fell asleep, they waited. In their sleep, they waited. Then they woke and went to the docks to wait some more.

Waiting had all the implications of living but without all the fuss, one woman thought. Certainly, it was better than not waiting, thought another. Waiting was exciting and dull at the same time, they all concluded silently.

They knew why the men left; they went to the coast of another continent, which they had been told was full of gold and savages. They would return with glory. The women fumbled over the word ‘glory’ in the morning when they sat alone at their dining tables or when they pulled weeds in the evening. Some of them imagined glory as they watched the sun set on the sea --but never during sunrises. The men used to shout glory but the women whispered it as if it were an innuendo for a body part they no longer had access to.

They didn’t count the days. They thought that would be disrespectful or even worse, doubtful of them. The day was waiting, hour was waiting, minute was waiting. Every day was the same day and it would be until they saw the ships growing in size along the shore with their men hanging off the sides waving with glory.

They lived in the Meantime. The women tended to the sugarcane and fed the chickens and braided their hair so that the ends wouldn’t split. They held their daughters' hands and went to the temples three times a week. When the daughters asked where the men went they would tell them “away”, knowing that was the truth.

The temples were as simple as the houses. They were composed of four stone walls and a thatched roof. The floor was dirt and the ceiling was palm fronds. In the center, the idols rested on wooden pedestals. The idols were manifestations of God himself. He had a sword as long as his body and two eyes that frowned. In every temple the statue bared his teeth, so the women always smiled with their mouths closed.

On the island they had no visitors. They were too far from the big landmasses and the neighboring islands didn’t dare – they were, of course, unaware of the disparity of men and surplus of women. Sometimes the women imagined what would happen if they were to find out. Sometimes they imagined good things to soothe themselves. Other times they imagined hell and all its details. In the Meantime, they were able to fill their minds with all sorts of nonsense.

The men were thick with algae by now, one woman dreamed. The savages were women too and had swallowed them whole, dreamed another without remorse. Dreaming is our fate now, they all dreamed.

In the days before the men left, dreams were bad omens. The future was for the future, the present for the present. Women’s dreams are wicked, a man said once. The dreams create a false and indulgent reality, seethed another. The women should not dream, the island agreed.

The women woke up later every day. If the men could see it, they would envision them as sleeping beauties frozen in wait for their princely kisses. The days shrank; the sun rose later with them and set quicker than they could finish their chores. The sun is withering away, one woman exclaimed. The moon is growing, another concurred.

They fetched the eggs from the chicken coops by candlelight. They beat their rugs under the stars. They huddled together to keep warm in the long, determined nights. The sun was definitely getting smaller, they all decided. But the dreams grew longer. They’d never had time to complete them before. The dreams were about every kind of thing. Some dreamed of harrowing adventures. Some dreamed of the men gone away. Some dreamed of the future, foggy and lonely. Some dreamed of the past, birth and marriage.

While they slept, their gardens grew, or rather, overgrew. The watermelon plants produced vines as thick as their necks. The maize fields sprawled for miles. The apple trees blossomed up into bouquets. Our dreams are seeping into daylight! One woman exclaimed as she swallowed an unholy chunk of pink watermelon. They’re growing in darkness! Called another after finding her daughter lost in the corn that stretched and stretched across the land. We have so much time time time to wait!

As their days shortened to hours – enough time to stuff their bodies with the sugar-sweet fruit of the day – their dreams collided. They woke warm and teeming with stories, which they told to one another. Connecting them and rediscovering them. Quickly, unimaginably quick, the women ran out of time to visit the docks. They lost the time to think of the men at all.

Finally, one day, a woman woke from her dream to discover she’d dreamt of them. They were salty-tongued, hands worn coarse by cedar. Another woman explained she’d dreamed of them touching something golden, lovingly lovingly golden. Another dreamed of the docks, no one there, only the peaceful empty docks.

The men returned that night. The boat creaked into the harbor unnoticed. The men turned to each other, petrified. The island was the wrong island. No women. No cries that they'd dreamed of or soft cotton dresses blue and dainty. As they stepped off the docks, they saw vines and weeds that encircled the village like snakes. They slashed their way through.

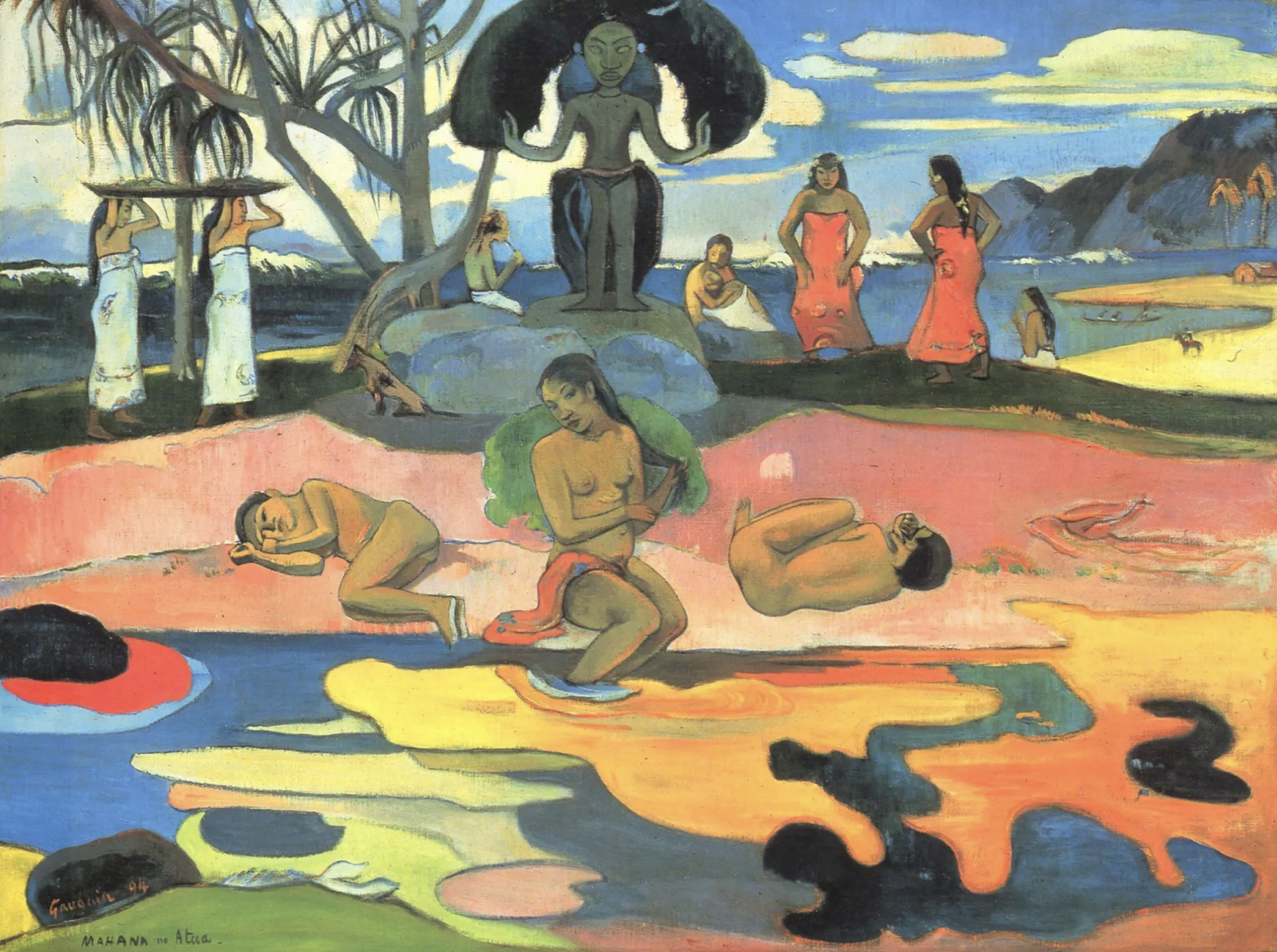

Artwork by Paul Gauguin, Mahana No Atua (Day of the God), 1894, oil on canvas, 69.5 × 90.5 cm, Art Institute of Chicago

Kayla Koontz lives in a cottage tucked in between two incense cedars in Northern California. Her writing focuses on otherworldly interactions, feminist themes, and perceptions of the "other" in all senses of the term.