The Historical is the Personal — Reflections on Postcolonial Guilt, Mi Koo Buns, and Writing History

I did not know that the Mi Koo [1] buns I used to eat for breakfast at my grandfather’s house on Sunday mornings have a history. Smack in the middle of their bright pink skin, there are five gashes radiating from the center, forming a clumsy floral design. I used to peel the skin and slice the freshly steamed bun in half. The next step was to slather butter on both pieces. It would melt immediately into the fluffy bread, leaving a golden patch that came back to taunt me in the cold mornings of my adulthood. Now, I am years and seas away from the simple anticipation of an eight-year-old waiting for the butter knife while swinging her legs underneath the antique table.

*

While watching the buns of my childhood, now on a computer screen in a university library in Abu Dhabi, I am unsettled. I am doing research on the communist guerrilla army in Malaya (now Malaysia and Singapore) who fought against the Japanese and British imperialists during World War II and the Cold War. When the banned documentary first arrived via an email notification, I dropped everything to collect the DVD from an expressionless librarian. He was stoically hunched over the reserves shelf, hovering his fingers over each title at a painfully slow pace until arriving finally at my order. Titled The Last Communist, this “semi-musical documentary” was made by Amir Muhammad in 2006. It was inspired by the memoir of Chin Peng, the leader of the Malayan Communist Party, who died in exile in 2013 in Thailand. His last wish was to be buried in his hometown of Setiawan, Perak, located an hour and a half away from my hometown. The Malaysian government denied his remains passage.

But what have Mi Koo buns got to do with communist insurgents? Everything, the film argues. It takes us chronologically through Chin Peng’s life by visiting the locations he travelled through in his political career. There is no narrator. The storytellers are the shopkeepers, bakers, plantation laborers, vegetable vendors, tour guides etc. who speak about their vocation and occasionally, their relationship with the past. Reading the captions on Chin Peng’s life in relation to the documentary of the mundane, the quotidian reality I am familiar with becomes imbued with history. I learn that the Mi Koo buns of my hometown are famous for their unique floral design. “Only in Taiping,” the long-faced baker declares in Mandarin. How this design came about is less famous. Decades ago, a young man who joined the Malayan Communist Party’s guerrilla army was caught by British soldiers and sent to prison, where he was tortured into a coma. His mother prayed for him every day at the River Goddess Temple on Temple Street, offering lotus flowers with incense sticks. One day, all the florists in town were out of lotus flowers. Desperate, the mother baked some Mi Koo buns, carved flowers on them, and presented these at the altar instead. The boy survived his coma.

Last summer, while interning at an Asian Studies institute in the Netherlands, I stumbled upon a book on the Malayan Emergency in the “free for all” bookshelf at the pantry. The Malayan Emergency: Essays On A Small, Distant War by Souchou Yao. Distant indeed. As a third-generation immigrant who grew up with middle class concerns, like how to get out of Malaysia, a failed revolutionary movement seemed completely incomprehensible, like the photographs and letters we found in my grandfather’s personal archive after he passed away. Bundles and bundles of relatives in China we know nothing of lay bound in rubber bands. A post-funeral gift from the dead. He left us no clues to make them legible.

*

“Where did your Malaysian accent go?” A close friend asked me after I came back from my first year at university. We were sitting at a café with sleek glass windows in Kuala Lumpur. “Give me a few days, it’ll come back.” Till then, he had to deal with speaking to a foreigner. I became very self-aware of my spoken English after that. Remember the lah’s, the meh’s the wan’s. Remember the Malay words, the Hokkien words, the Tamil words. In truth, I knew my Manglish had dissolved like salt in the sea. As I fill up my senior capstone proposal two years later, I bite down the anticipation of embarking on a journey to the juicy forbidden. I grew up learning that the communist insurgents were terrorists in an insignificant but unfortunate chapter of our national history. Like the methane of decomposing bodies, inherited memory somehow always finds its way to the surface. A trigger, like the subtle reproach of my friend, is the spark needed to start a forest fire. History is closing in on me, and no Western country can save me from my guilt.

*

“What is the archive for a memory that was decimated by colonial powers and actively suppressed to this day?” I asked my professor a few weeks ago. We had just read Arlette Farge’s Allure Of The Archives, in which Farge describes her experience of looking through police surveillance documents in 18th century France in the Paris Archives. They were incoherent transcriptions of splintered conversations and scattered observations. Farge notes with delight how these fragments capture what the archive itself rejects, and how this tension reveals “history as it was being constructed, when the outcome was never entirely clear”[2]. Enchanted as I was by Farge’s poetic prose, I could not help but be bitter. Fragmented as they were, at least the proletariat’s subjectivity was preserved. What about my grandfather’s? The historical has become the personal.

In The Combing of History, David Cohen writes that there are “multiple locations of historical knowledge”, and only by “recognizing the spacious and unchartered reservoirs of historical knowledge in present and past societies [can we] begin to think more clearly about the forms and directions of historical knowledge…”[3] As I start collecting the various fragments of a memory smashed by successful British and nationalist propaganda, I am finding that some of the richest locations of historical knowledge are situated within my memory. That surreptitious memorial plaque by the haunted waterfall my parents forbade us to swim in? It was actually built to honor the guerrillas who fought against the Japanese soldiers during the brutal occupation. The Chinese high school that was my mother’s alma mater? It was a school known for its communist sympathies, and where teachers would beat anti-imperialism consciousness into their students. The Chinese-concentrated area my mom and her siblings grew up in, and the constant subject of their nostalgic conversations? Just two generations ago, it was a concentration camp built by the British colonial government to isolate the communist guerrillas from their Chinese-majority support base. I am not recalling evidence or even anecdotes that are useful for my research topic. Rather, I am starting to look back and recognize the everyday of my reality as a product of a history that is worth paying attention to. In other words, I am an archive.

Like my parents, I was an inactive carrier of the memory of our civil war. Somehow, an alignment of random chance and privilege has caused a mutation in the gene of silence. I find myself fervently gathering every insurgency-related fragment from libraries and archives around the world. The expressionless librarian might have caught on to my impatience. His fingers hover slower each time. But every time I open the book, or the document, or the DVD case, the ghosts rise howling. I hear the planes carpet bombing our tropical rainforests. I hear the wailing families forcefully removed from their ancestral homes. I hear the fading heartbeat of a husband bleeding to death at the fringe of the jungle, begging his wife to leave with their comrades before the enemy closes in.

But I have also been listening for the silences. I cannot force the mute Mi Koo bun to tell me its story, but the silence surrounding its incredible origin says something about how the censorship of the history it is associated with trickles down. The closed doors I keep encountering in my search for primary sources also speaks, albeit with bureaucratic language. “Special permission is required for materials related to the Malayan Communist Party at the Arkib Negara[4],” a Malaysian scholar writes to me. But if I stick my ear against the door, I hear fear. A fear inherited by the present government from the past government, who inherited it from the British colonial authorities, who shared it with their American counterparts across the ocean during the Cold War. A fear that was global in scale, local in its casualties. A fear that stretched across time, across subcontinents: evolving from the fear of a British ethnographer in India when confronted with identities he could not neatly categorize, to the fear of a contemporary Malaysian politician who cannot foresee how ethnic tensions will escalate should the narrative of our hard-won independence shifts. The fragments cannot be put back together, but writing about how they came to be hits back at power with the force of a million clenched fists, raised.

*

Sunday mornings at Grandpa’s were always a quiet affair. As a child, I revered and feared him. I would stare at him from across the table, Mi Koo bun in my tiny hands, while he cracked a raw egg into his rice. “That was how they did it in China,” mother explained, while peeling baked sweet potatoes, her favorite breakfast.

“You wasteful children,” he would growl from across the table when I turned away from my mother’s hand trying to feed me potatoes, “the sweet potatoes were all we had to eat in those camps.”

***

[1] A Malaysian-Chinese bread. “Mi Koo” roughly translates into Tortoise Bun.

[2] Arlette. Farge, The Allure of the Archives, Lewis Walpole Series in Eighteenth-Century Culture and History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 107, 113.

[3] David William. Cohen, The Combing of History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 4-5.

[4] Malaysian National Archives.

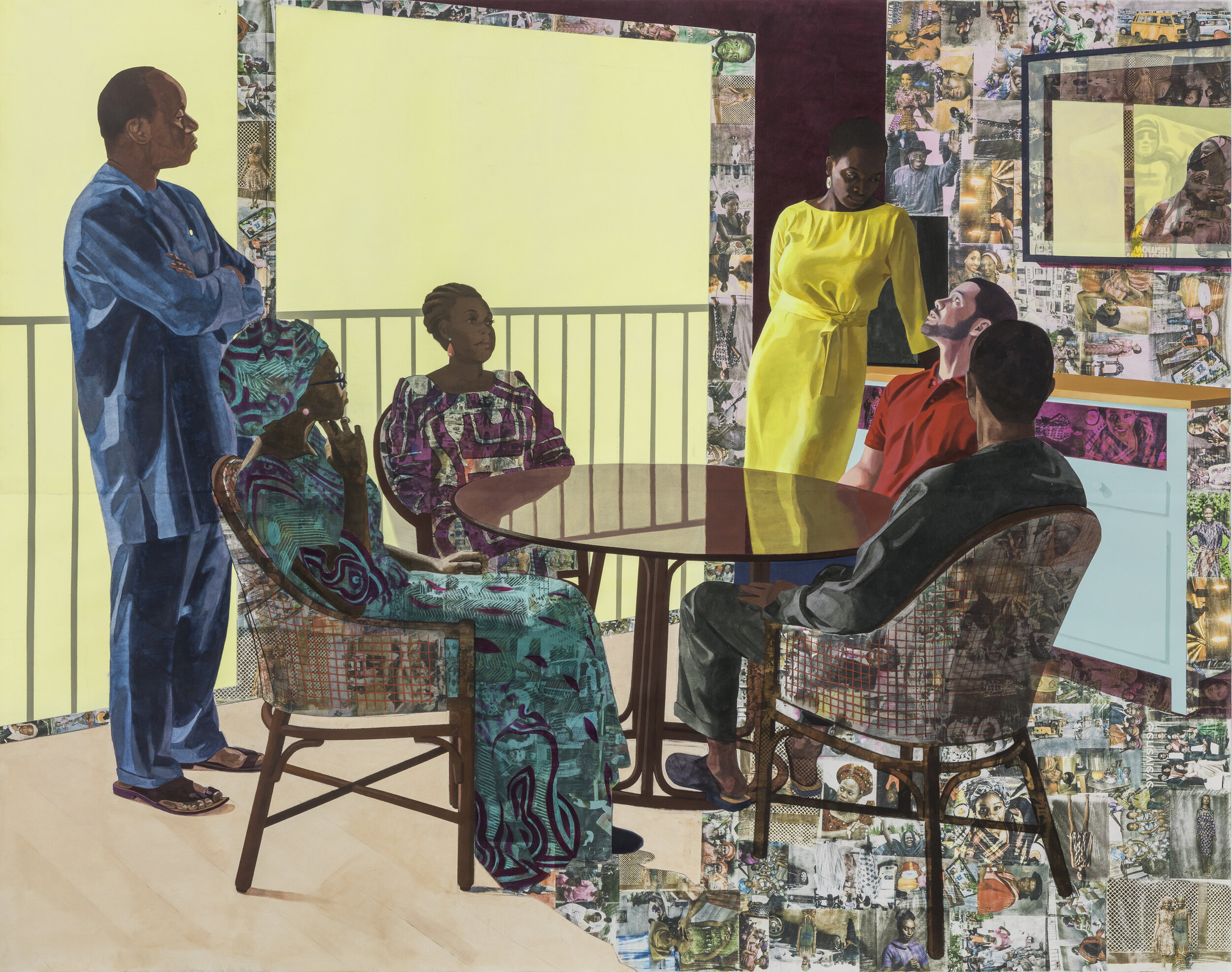

Artwork by Njideka Akunyili Crosby, "I Still Face You", 2015.