Notes on Kendrick Lamar, Moby-Dick, and the Margins

It was always me versus the world

Until I found it's me versus me

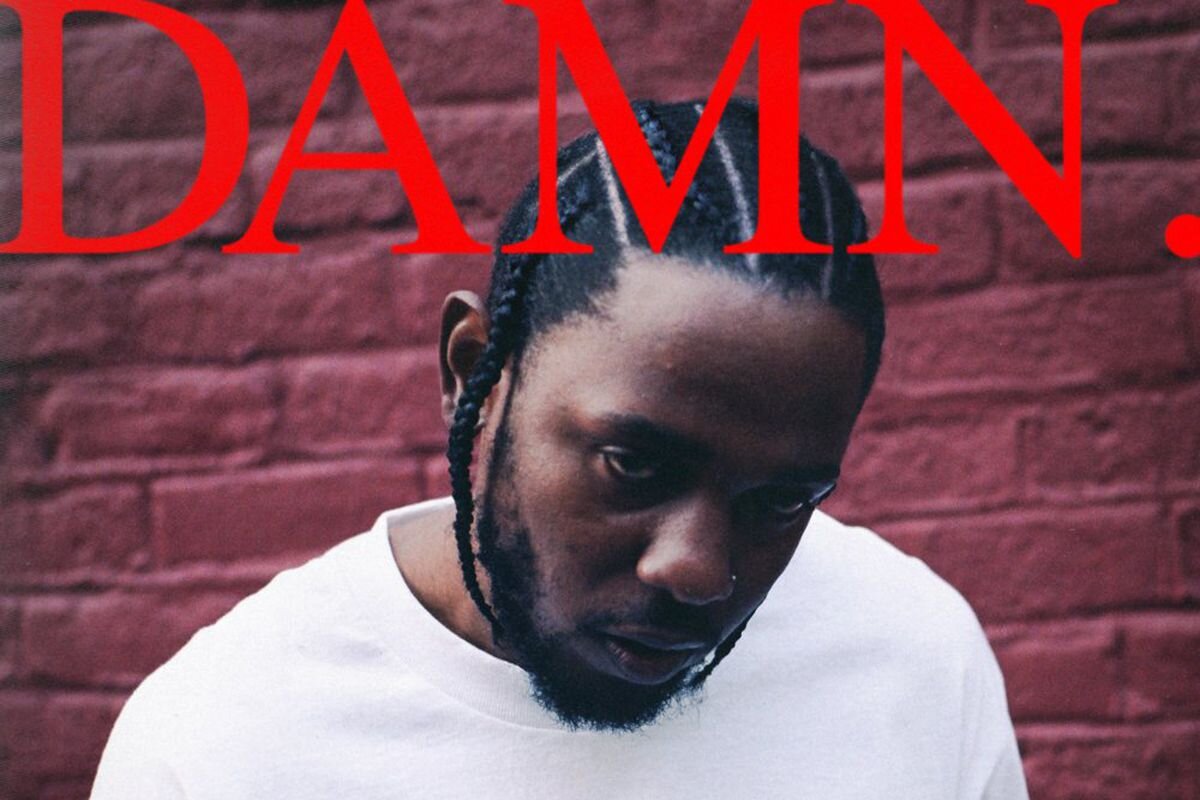

Kendrick Lamar’s 2017 album DAMN. is a phenomenal project. Immediately following To Pimp A Butterfly, possibly Lamar’s most accomplished album to date, DAMN. had initially threatened to be a less subtle, more reactionary work when compared to the intricate patchwork woven by To Pimp A Butterfly, especially when singles such as “DNA” and “HUMBLE” were released. Compared to the heavy-handed, anger-driven lyrics of these singles, DAMN. in its entirety, also features pieces by Lamar in which he reflects, mellow and quiet, on his black experience. As opposed to the “creation of a new site where the violence of internalized racism and fear sublimated into rage can be transformed to target institutionalized racism” in To Pimp A Butterfly, as Siebe Blujis writes in “From Compton to Congress,” DAMN. wants to create a new space for Lamar in which ‘rage’, both against internalized and institutionalized racism, is synthesized into something else, a reflection, a “me versus me” rather than a “me versus the world”.

Here I cite Lamar’s “DUCKWORTH”, the final track from DAMN, where he raps about an encounter between Anthony “Top Dawg” Tiffith, owner of Lamar’s record label Top Dawg Entertainment, and Lamar’s father Kenny Duckworth many years before Lamar’s own meeting with Tiffith, leading to the birth of “the greatest rapper…from coincidence”. Lamar doesn’t know how it happened – what led to this coincidence? The very nature of the word ‘coincidence’ would point one to the fact that, well, nothing led to it. Tiffith, Lamar tells us, could have killed his father, Ducky, who worked at a Kentucky Fried. But Ducky chose to get on Tiffith’s good side, leading Tiffith to spare Lamar’s father’s life. “That one decision changed both of they lives” – “Because if Anthony killed Ducky, Top Dawg could be servin’ life / While I grew up without a father and die in a gunfight”. If nothing led to it, then it must be either have been fated , or it must have been that on Tiffith and Ducky’s parts, there was a profound agency that could change the course of history. Here, there is a constant disagreement and tension between these two forces – divine determination and human agency – as captured by the following lyrics:

Pay attention, that one decision changed both of they lives

One curse at a time

Reverse the manifest and good karma, and I'll tell you why

You take two strangers and put 'em in random predicaments

Give 'em a soul so they can make their own choices and live with it

Twenty years later, them same strangers, you make 'em meet again

Inside recording studios where they reapin' their benefits

Then you start remindin' them about that chicken incident

Whoever thought the greatest rapper would be from coincidence?

The “curse” refers to, as does Lamar earlier in the song “FEAR”, the curse of damnation from the Book of Deuteronomy, from the Old Testament. Many different currents of Christianity have historically responded in different ways to the notion of damnation. Lamar wants to figure out his way of responding to damnation: it is by making a choice, by “reversing the manifest” with “good karma”. It could have been fate for Lamar – fate might have led to the salvation of his father (and ultimately to his own salvation and, by extension, to the salvation of black Americans). But Lamar asserts that he does not want to rely on fate, for fate is not under his control. This is part of what it is to be from the margins – a desire to be in control of your own destiny. And perhaps the fulfillment of that desire leads to a Kanye West, who will assert that 400 years of slavery sounds “like a choice”. In other words, someone like Kanye, who has reached an advanced enough social and economic position to think wrongly that he is in absolute control of his destiny will extend this control to those instances of true, evil oppression. For anyone else, it is a limitless desire, for one can never be in full control of their own destiny. Hence the desire is self-renewing, leading one to develop the desire to desire control over destiny, and so on ad infinitum. When one develops the illusion of having fulfilled this desire, then he becomes a Kanye. Until then, he is, like Lamar, in search for a resolution of those conflicting forces that rule life – and one of those forces is agency.

Though I cannot tell why it was exactly that those stage managers, the Fates, put me down for this shabby part of a whaling voyage, when others were set down for magnificent parts in high tragedies, and short and easy parts in genteel comedies, and jolly parts in farces—though I cannot tell why this was exactly; yet, now that I recall all the circumstances, I think I can see a little into the springs and motives which being cunningly presented to me under various disguises, induced me to set about performing the part I did, besides cajoling me into the delusion that it was a choice resulting from my own unbiased freewill and discriminating judgment.

What motivated me to write about Lamar’s conception of agency and the tense relationship he suggests between agency and divine fate and determinism, is Herman Melville’s 1851 novel Moby-Dick. The novel’s narrator Ishmael is constantly in search, like Lamar, for those driving forces behind his life. Why he joined a whaling voyage doomed to fail is beyond him. But after the voyage has failed and his shipmates have all died, Ishmael does not know what to think. It leads him to such a profound sense of emptiness that, I propose, he calls himself Ishmael, making him the only other person onboard the whaling ship Pequod apart from the infamous monomaniacal Captain Ahab. Ishmael, as we know, is Abraham’s child from the Egyptian slave-woman Hagar, who in the Biblical tradition becomes an outcast and in the Islamic tradition becomes the ancestor of the Arabs. In the novel, too, Ishmael becomes an outcast, surviving the shipwreck by literally being in the margins of the vortex that swallows the ship and everyone on it. Being from the margins, Ishmael wants to be in control of his destiny. When he realizes, after his shipmates have died, that he was not, in fact, in control, he tries to impose control after-the-fact, by owning his identity as a marginal character, by calling himself ‘Ishmael’, by trying to make himself at least as important as the central, powerful, all-consuming character of Ahab.

Unlike Ishmael, Lamar too currently wants to imagine that he is in control of his actions. In “DUCKWORTH”, he wants to extend control beyond his own life over the black experience. These two characters, Tiffith and his father, both archetypes of the black American gangster and the well-meaning, do-gooder black American respectively, make choices that, regardless of the two characters’ backgrounds and motivations, result in the rapper Kendrick Lamar. In a particular way, Lamar too is imposing control upon history, like Ishmael, by narrativizing it. He seems to want to conflate the freedom that he has to make choices that will impact his future with the idea that the coincidences that affected his life were also within his control, an extension of his own freedom.

Synthesis

In this “Notes”, I wanted to articulate Lamar’s desire to find an alternative vision to his “me versus the world” from To Pimp A Butterfly. But in finding this alternative in “me versus me”, Lamar wrestles with complex and paradoxical notions of fate, agency and divine determinism. He needs to do this because he is from the margins, just like Melville’s Ishmael from Moby-Dick. And as a character from the margins, he ends up conflating his own freedom with the freedom (or lack thereof) of others, with a desired freedom from institutional racism and inequality, resulting in a challenge against something beyond him, a challenge that is both radical and existential..