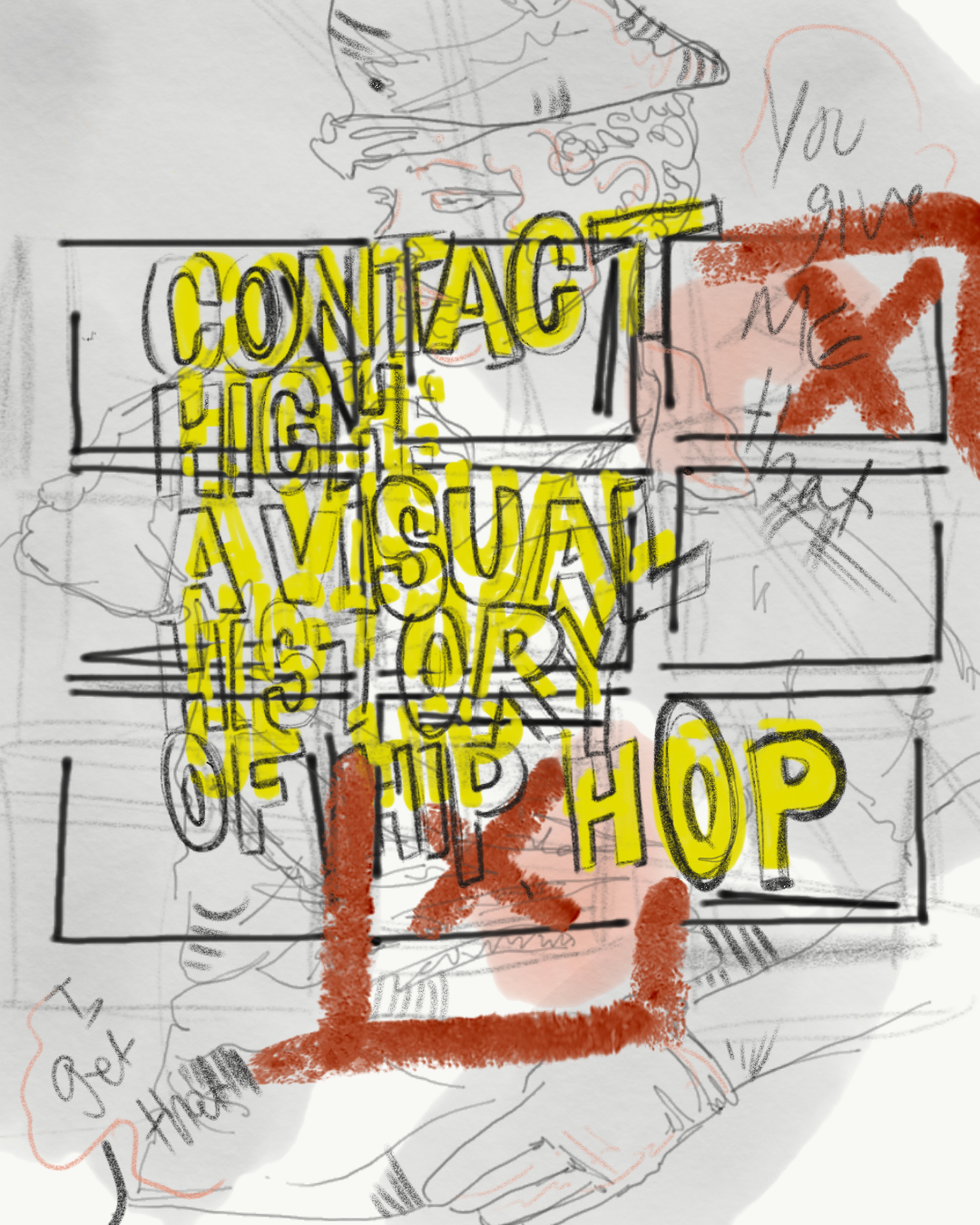

You Give Me That Contact High

Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop began as a book, written, to my surprise, by a white-passing woman. Vikki Tobak is a writer, journalist, and curator who authored the historical music photography project, now an exhibition at Manarat al Saadiyat in Abu Dhabi, UAE.

This is the exhibition’s first trip abroad. Previously shown at Photoville New York in 2018, Los Angeles’ Annenberg Space for Photography in 2019 (where it holds the record for the best-attended show in the foundation’s history), and New York’s new International Center of Photography in January 2020, Contact High now makes its international debut within a region where hip-hop culture is a recent but steadily growing craze.

The exhibition comes in partnership with Sole DXB, a platform that celebrates streetwear and hip-hop culture in the UAE. Apart from operating a creative agency and print magazine, Sole DXB is most renowned for hosting an annual cultural festival in Dubai with booths and pop-ups showcasing contemporary art, clothing, and merchandise from international and local brands. It also hosts major musical acts such as slowthai, Black Star, Koffee, Masego, Rico Nasty, Wu-Tang Clan. In December 2019, Sole DXB saw 36,000 attendees, a testament to how popular hip-hop culture has become in the UAE. It makes a perfect harmony, the collaboration between Sole and Tobak’s curatorial project, which aims to encapsulate the trajectory and cultural memory of a genre that has animated these two enormous creative projects oceans away from each other.

On my first visit to Contact High, as an avid hip-hop fan and photographer myself, the first thing I notice is the other people. The exhibition space is ample, almost the size of a football field. Scattered groups of mostly Arab youths teem around the photos, taking pictures of each other next to portraits. Most of them are dressed in black, donning edgy sneakers and contemporary streetwear. To me, they become part of the exhibition experience. I watch a pair of young men—for lack of a better word—squeal as they approach a glass case displaying rapper MF DOOM’s mask. (The recent death of DOOM now makes this display even more poignant and potent.) I am slightly surprised by the overt enthusiasm. I remark to my friend, visiting the exhibition with me, how being here feels like an extension of being at Sole DXB, where I once pumped fists amid a sea of arms and mouths raised toward the guitar gospel of Blood Orange.

The UAE, like many countries around the world, is besotted with hip-hop culture. A musical genre borne from the more unsung boroughs of New York has quickly metastasized into a global phenomenon, seeping into mainstream culture, fashion, and visual aesthetics and design. Rappers and hip-hop artists are elevated to mythical, godly status, and their style of speaking, aesthetics, clothing, and general attitude are considered “cool,” particularly among the Internet-driven generation of youth.

At its root, hip-hop is a Black art form. Early hip-hop and rap stem from and owe Black literary giants such as Gwendolyn Brooks and Langston Hughes from the Black Arts Movement who pushed for asserting Black English and African American Vernacular English (AAVE) within mainstream poetics. The first rap groups, such as the Last Poets, drew inspiration from their work, which eventually led to the birth of early hip-hop formats that morphed performance poetry into freestyling and built on rap’s important storytelling component that taps into narratives of a Black collective consciousness. Hip-hop began as a way of articulating the urban decay and poverty blighting Black communities in the US, and it helped restore the vitality and pride of African-American culture. It was an outlet and a reclamation for a massive community.

A few weeks ago, I paused an Instagram story written by a Black artist based in the UAE, expressing apprehension about how some non-Black attendees of Sole DXB seem to utilize and approach the space as a site to fetishize Black art and aesthetics while remaining complicit to the systems that continue to put down Black people socio-economically. I stopped to think. I loved attending Sole DXB, and as a non-Black person, I wondered how my participation within this larger project may be felt by the very Black people whose history and lineage are rooted in this genre now hailed as a “global phenomenon.”

There is a tricky line between genuinely enjoying and celebrating a culture, and adopting and fetishizing it while ignoring its roots, history, and cultural value. There is a hurtful gap in our vision and approach to enjoying “foreign” cultural experiences that become trendy and cool if we are not also making the effort to appreciate that experience’s historical value to a community, especially when that community has a long history of being marginalized and oppressed in all manner of ways, ranging from economic barriers and the deprivation of rights to open discrimination, enslavement, and general cauterization of culture and identity.

A family friend once remarked, on a warm Friday night over fries in Gaborone, how “the rich kids here love to act like the poor kids in America.” I was much younger then, but this line has stayed with me, especially as I have come to live in the UAE. Sometimes I wonder, slightly suspect, at precisely how much respect is involved within the worship of hip-hop culture here. It is no secret that there is much wealth and privilege in this country. That countless young people can afford, from birth, the kind of luxuries that rap artists in the U.S only brag about on hit tracks once they’ve “made it.”

But no perspective is this narrow; if it were, it wouldn’t be true, because the truth is always infinitely complex. There are many people in the UAE who genuinely believe in what hip-hop stands for, and I am one of them.

I began listening to rap seriously, as a medium of finding catharsis and pleasure, when I went to Paris. It was a precarious stage of my life. I was making many mistakes. All the mistakes of being young and privileged. I was also living in a “white” society for the very first time. I felt thrown out of myself and what I had always known and established about the world was left disassembled. I couldn’t handle the exacerbation of my emotional, if not physical, isolation. So I turned to the music that had perfected the sounds of such a feeling.

A friend in high school had tried getting me into rap but failed. I had had to make the journey on my own. I finally listened to all the Kendrick Lamar he recommended; I sat in my dimly lit dorm in the 14th arrondissement staring into the corner, earphones in and heart pounding. I fell in. Mac Miller, Riz Ahmed, Rejjie Snow, Amine, A Tribe Called Quest, and so many others, rapping about different kinds of pain and highs mixed together, slathering words with old and new jazz beats and samples, making something so incredibly striking out of all the hard, scattered rawness of personal experience. It was what jazz once did for a generation, but with the hardness and newness of a later, rapidly globalizing age.

In the official pamphlet for the Contact High exhibition, stacked neatly at the entrance, there is frequent mention of hip-hop being about “self-definition.” The photographs and fashion on display help to “visualize [the] self-definition, identity, and self-representation” that characterizes the emergence of hip-hop culture. The pamphlet introduction specifically notes that “Self-definition is one of the characteristics of Hip-Hop, especially when it comes to visuals and style. From a young artist freestyling on a corner in Brooklyn to an anonymous b-boy popping in a nightclub to a worldwide sensation, photographs tell the story. For artists, that one significant pose or press shot or album cover would play a major role in shaping them into icons known by their personal attributes–skills, style, swagger, bravado and likely even a fresh pair of sneakers.”

While hip-hop may be a Black art form, at its core, it is universally a vehicle for the reassertion and reclamation of both personal and collective identity. Perhaps that is what made the genre so prime for migration into Arab communities. Arab hip-hop artists, such as El General, Deeb, and Syrian rapper Omar Offendum took important cues from the emergence of hip-hop. They saw it as a tool for civil resistance against harsh living conditions; it expressed and depicted the frustration felt by many in the politically tumultuous Arab region. “Rap is poetry at the end of the day…and that is something that Arab culture can definitely associate itself with,” Offendum once said in an interview.

In another instance, rapper Public Enemy compared hip-hop to CNN, suggesting the art form was important for broadcasting and connecting the socially concerned voices of minorities and oppressed communities. Hip-hop provides an artistic platform to promote solidarity based on shared cultural and ethnic experiences. In an online video, Offendum actually pays homage to the roots of hip-hop by reciting Langston Hughes’s jazz poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” and then rapping the poem in Arabic, which is often regarded as a language of poetry. The rivers of the past that united Black culture for Hughes now provides unity and pride to Arab culture as “The Arab Speaks of Rivers.”

Perhaps the explosion of hip-hop and hip-hop culture in so many countries may as well be attributed to the core expression of the genre in articulating lack of belonging, of not fitting in, of being an outsider. It is ultimately my own feelings of isolation and outsiderness in a foreign culture that pushed me headlong into the world of rap, to lyrics that were unafraid of laying bare serious socio-cultural and economic realities. And these feelings can persist regardless of what economic privilege you possess. No one is immune to pain. Maybe there are people in the UAE who interact with hip-hop culture at the surface level of a trend, but there are also undoubtedly countless people who genuinely resonate with how hip-hop and rap functions and plays out in their lives. Local rappers, such as Dubai-based Kafv, blend their unique experiences of living in the UAE, a country mostly made up of immigrants, into their music and lyrics. Hip-hop is translated into a new socio-cultural landscape, and there is infinite possibility for innovation and reassertion of all kinds of “othered” identities within the genre.

*

Vikki Tobak, the creator of Contact High and the co-curator of the exhibition (along with creative director Fab 5 Freddy) immigrated to Detroit, Michigan at the age of 5, from Soviet-era Kazakhstan. In an interview given to journalist Ben Merlis for udiscovermusic.com, Tobak commented on her early musical experience. “I landed in Detroit–a predominantly Black city, predominantly music-oriented city, where music is everywhere you go. You hear Motown, you hear Aretha and Stevie Wonder, that was my impression of what America was from the start." In Cold War America, some of her white classmates often treated her with mistrust, whereas the Black community, she says, welcomed her with open arms.

Detroit was Tobak’s site of immersion into hip-hop culture. My initial surprise at finding out that Contact High was created by a non-Black person slowly made more sense. I imagine that Tobak’s surroundings and community in Detroit and later the hotspot of New York, coupled with her own experiences as an immigrant in the U.S.A and possible feelings of outsiderness, led her to form a great bond with the genre.

Tobak went on to lead an exciting career as a cultural reporter and journalist, segueing into music journalism and photography curation, the resulting expertise of which manifests in Contact High. The 2018 publication of the book led to it being considered as one of Time Magazine's 25 Best Photobooks of 2018, while the New Yorker described the publication as a "Wondrous tribute to the way hip-hop overturned not just the sound of culture but also ways of seeing."

Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop offers an “alternative insight” into the evolution of this now global genre. The exhibition presents an archive of contact sheets and artifacts, including clothing and sneakers, and provides a more intimate glimpse into a time when hip-hop was just beginning to bloom. Large blow-ups of iconic photographs, magazine covers, and album covers (printed with the help of Dubai-based Gulf Photo Plus) are accompanied by the contact sheets in full, complete with mark-ups made by the photographers.

Putting up the full marked up contact sheets is a curatorial decision that not only grants us access to the photographs and their subjects, but also into the minds of the photographers and the process of choosing the right image. One can see the shortlisted images, marked with asterisks, and the clear crossed-out rejections. Choosing the right image is also an act of curation, one which we may be now over-familiar with in the Instagram age. Curating the image that may represent us as an artist is a process of directing or practicing agency over the circulation of how we are or choose to be perceived, of how we brand ourselves to the world as creators and creatives.

As a photographer myself, apart from being drawn to the general style of photography on display – intimate, nostalgic, sentimental, candid – which has similarities to my own, I am particularly attracted to this display of the photographer’s process via the contact sheet. Even the word “contact” implies a tactility, a soft touch, a closer grasp, of what used to be a community that felt distant, unreachable, mythical even. The choice of photographs themselves stray out of the ordinary; the chosen shot of Kendrick Lamar for example, is a slightly blurry, meditative one of the young rapper lying on a couch in the studio thinking up lyrics. A large blow-up of Tyler the Creator has him pulling a quirky face, aptly illuminating his personality. The chosen shot from the contact sheet containing images from Mac Miller’s studio, has the final image chosen as a shot of the late rapper’s tattooed hands upon a piano.

In a way, the contact sheet preempts the Instagram photo dump or reel. The digital revolution has forever transformed the way we relate to and access celebrity culture and consequently hip-hop culture, photography, visuals, music, and aesthetics. We can now chat to and watch our favorite rappers and artists live in real time; we can share an artsy, candid shot of an artist in the studio with a quick tap to thousands of followers. Social media, particularly Instagram, has completely changed the landscape of photography and its circulation. Thus, it has changed how culture migrates and is transmitted. It has changed how we archive cultural memory and daily life, it has changed the boundaries between celebrity culture and ordinary life, elevating the quotidian realities of both to more equal commonalities.

Which is precisely why, at the end of the day, the arrival of Contact High to international shores feels so special. Its celebration of older analog photography, within the larger archival project of arguably the most important musical genre and cultural and aesthetic explosion in recent history, from an era still on the precipice of the digital revolution, is not only sentimental but also important. The way we relate to and document culture will never again be the same. Crystallizing and curating an important historical narrative and its evolution is an act of service and homage to a culture’s roots.

Ultimately, hip-hop is indeed the global phenomenon du jour; it taps into the universal pain of feeling and being made to feel like you’re not enough. Hip-hop is inherently resistant, and this complements human nature, which is built to fight and adapt to changing and often destructive surroundings. The way hip-hop has spread itself like slick jam on the toast of every continent, actually makes me go back to thinking about language. When I was younger, I was convinced music theory was also a language as much as French or Hindi or English was to me. And that music itself could speak in a way that couldn’t be coded in words, so we had to make several signs and symbols for it, give it its own unique script. Hip-hop’s cosmopolitan-like travel across the world is reflected in the various translations of it. But more importantly, when we consider it as a language, we open up the space for more forms to emerge in the future that may operate in the same way, connecting with people across different conditions and cultures through its core aim, which is to communicate ideas and feelings.

Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop is open daily (10 am to 8 pm) from December 15, 2020 until May 31, 2021 at Manarat Al Saadiyat, Abu Dhabi, UAE. Cost of entry is AED 30.

Artwork by Myriam Louise Taleb