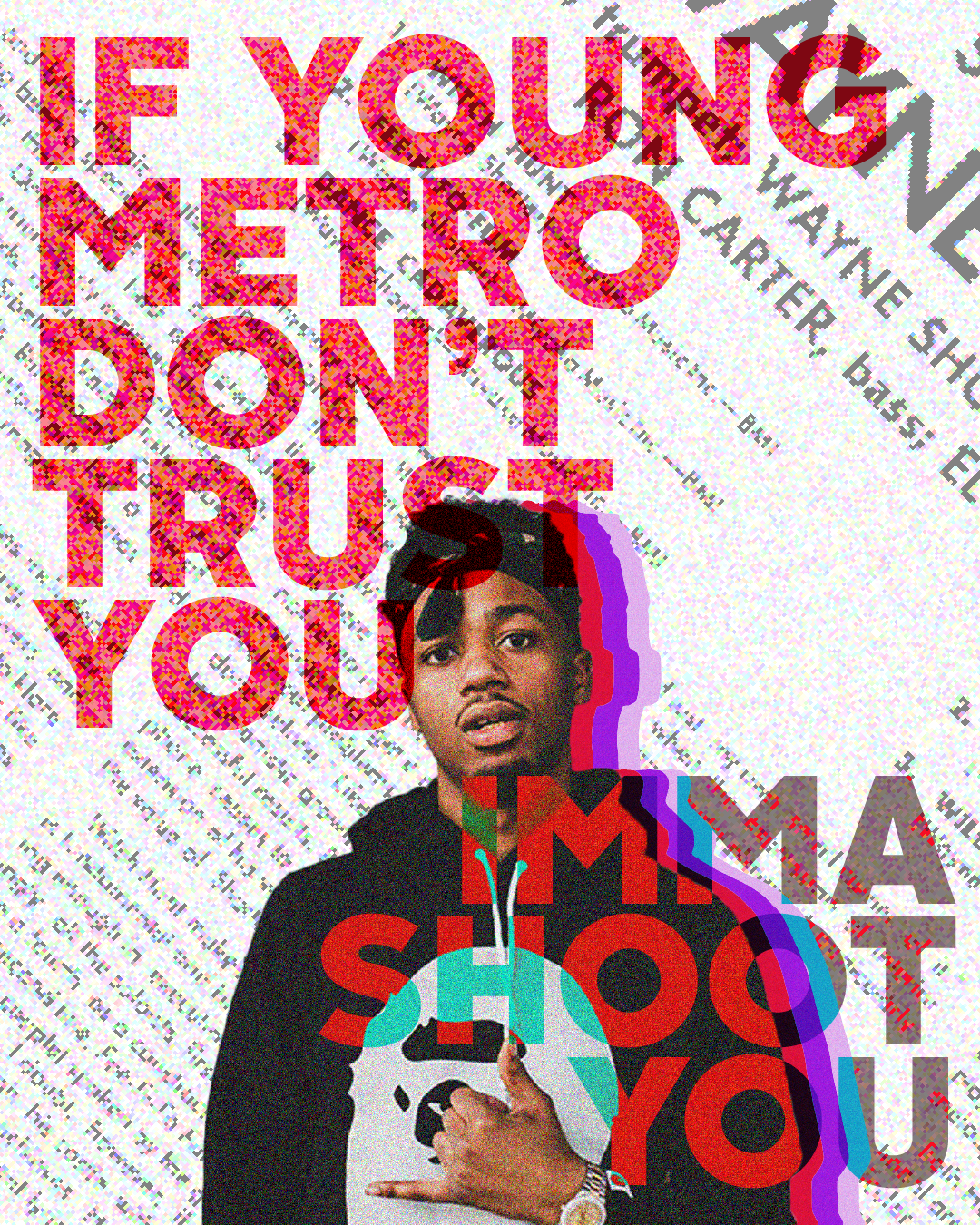

If Young Metro Don't Trust You, It’s Not Nice: Producer Tags, Ego, & Excellence

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you think of Jason Derulo?

Is it his careful falsetto? His newfound TikTok fame? His Adonis-esque abs? Perhaps his obsession with derrière?

The first thing that comes to mind for me is Pokémon. Here’s why.

Jason Derulo is incessantly ridiculed for singing his own name at the beginning of tracks, but he’s hardly the only one touting a signature phrase. Pitbull’s “Mr. Worldwide” moniker was one of infamy, as was T-Pain’s signature autotune and DJ Khaled’s “We the best!”

These phrases are producer tags — sonic watermarks at the beginning of tracks that serve as signatures of the producer. Producer tags originated from DJ and mixtape culture in the 80s and 90s when disc jockeys would shout their name during their performance, mostly to help with transitions between tracks.

Historically, producer tags served a predominantly utilitarian purpose, which makes the following TikTok video more curious than ever:

This is a remix of “Baby Pluto” by Lil Uzi Vert, with 24 producer tags crammed into the introduction as the beat loops again and again. And it has over 4 million views.

A quick scroll through user @macaronipenis’s comments reaps overwhelmingly positive comments, with many people requesting their favorite producer to be included in the next remix. (Spoiler alert, @macaronipenis delivers.)

Well, you might be thinking, “An object of the Internet outgrew its meme lifespan and is now unironically popular. Hooray.”

But hooray for who? Producer tags were purely functional assets of music production — what role do they hold now? Had producer tags just been under our noses the entire time, waiting to strike with virality? And how does that affect my weekly TikTok scrolling sessions?

The truth is that audiences have always been aware of producer tags, especially at live events. DJ Booth’s Dylan Green writes about an incident with DJ royalty Funkmaster Flex, who constantly interrupted his performance to shout out his tags and his name. The “tag-heavy approach” broke the audience’s groove and brought the energy of the performance to a grinding halt, earning him a symphony of drunken boos.

In a recording context, producer tags historically played a lesser role than they do in live settings, simply signposting a coherent experience for the listener, with as much aesthetic intention as the typical white-text-black-screen film end credits. Many producers like Dr. Dre or RZA chose to let their sonic aesthetic speak for themselves. Other producers begrudgingly accepted their place, tucked deep in the liner notes of print albums.

Then the Internet happened and re-prioritized the producer tag — eventually, that is. A few dominoes had to fall in place first for the significance of the producer before the producer tag could even come into the spotlight.

One, a lower point of entry. The Internet nullified the technical mysteries of the production process, opening the floodgates for an ocean of young producers. Countless online resources began to pop up for emerging producers: Instagram tutorials from neighborhood educators, online EDM classes by deadmau5, forums to debate microphone polar patterns. It became easier than ever before to begin production on your own.

Two, a platform. Outside of highly curated award shows, producers had only received recognition in liner notes. These young producers now had a place to share, publish, and claim their work. This was unprecedented power to producers, who had traditionally taken a backseat to the vocalist, barring those in the echelon of legends. With the platform came direct interface with an audience that became more well-versed in the intricacies of production, thanks to the aforementioned lower point of entry. This audience wanted to know more about and engage more with the behind-the-scenes details that were previously inaccessible.

Three, the popularization of hype. Democratizing art meant that it became easier to create work across mediums, so now every aspiring producer’s breakout track has an accompanying music video with the usual fast cars and foxy women. Music became inseparable from the culture of flexing; together with social media, hip-hop established high expectations for the luxuries of becoming a rapper. In the article “How Hip-Hop Left A Lasting Influence on Streetwear & Fashion,” Jian Deleon writes that “movements like punk were founded on anti-fashion ideals and stood in contrast to consumption and capitalism. Hip-hop fully embraced it from the start, seeing dressing up as its own competition — and every rapper boasted he dressed better than the rest.” Hip-hop had always been about hype, but that hype eventually became visible and ubiquitous.

The combination of the three, plus a dash of Chemical S (for streaming services), resulted in an exponential increase in content on the Internet. Endless EPs and singles, exclusive releases and increased exposure. As metrics drove audience consumption and artist compensation, music producers slowly became content creators, their creative direction puppeteered by streaming giants like Spotify, Pandora, Apple Music, and Tidal.

Streaming services dominate our listening habits these days, especially in how we discover and enjoy music. The ease of access to new music has diminished our attention span; music blogger Paul Lamere studied Spotify’s advanced user analytics in 2018 and found out that 28.97% of all users skipped to the next song within the first 10 seconds of the track.

Content consumption determines how content is created; after all, we must get those sweet engagement stats up. For the producer, that means they have to draw the listener in as quickly as possible, before they skip the track. The solution is composing shorter songs at a faster rate, a phenomenon that has been widely reported as a direct result of streaming platforms and algorithms.

Lil Tecca featuring Juice WRLD. Who’s the producer of the original beat? Who did the remix?

But producers began to face an unprecedented problem: there was an overwhelming supply of content, and none of them sounded distinct enough to be recognizable. The worst part was how streaming services credited producers — or rather, how they didn’t. For print albums, producers were relegated to liner notes, but streaming services bury the producer’s name deep in the track’s metadata (as is the case of Apple Music) or remove it completely (as is the case of Spotify), featuring only the main vocalist as a clickable link.

Producers are entering an industry with a whirlpool of short synonymous content, with no clear avenue of identifying the creatives behind the beat.

Well, re-enter the producer tag — this time with a vision.

Producers realized that their tags needed to tell the audience more than their name. Tags needed to encapsulate who they were as artists. The tag became an elevator pitch: it leaves the audience wanting more from a producer. In the words of James T. Green for The Outline, it must be “sticky, memorable, and [evoke] the listener to sing along, like a chorus.”

Soon there was a tag-naissance with the advent of drill and trap as centerpieces of mainstream hip-hop. As tags became more prominent, they became more recognizable and distinct. Nowadays, a great tag includes a reference to the producer’s name, and a distinct style that pays homage to the producer’s own stylistic approaches to music. Producers like Metro Boomin even have an entire section on Wikipedia dedicated solely to his producer tags.

In a lot of ways, a great producer tag can actually elevate the track; in a Genius video quiz of producer tags, this was the top comment:

The genius (no pun intended) of it all is the universality of the producer tag. It must be catchy enough for the casual listener, but contain enough Easter eggs that it is enviable to fellow producers. The inverse is also true: an ill-conceived producer tag that serves no aesthetic value beyond function — like that of Jason Derulo — rightfully gets critiqued as an incomplete form of artistic expression.

As an example, let’s take a look at the tag for Viriginia-born producer Lex Luger, the producer who contributed to the rise of Waka Flocka Flame.

In the track “B.M.F.” by Rick Ross, Lex Luger’s tag begins at 00:14: a group of staggering, ascending triplets (notes in groups of threes) reminiscent of shooting lasers. The triplet melody is a reference to Atlanta’s trap sound, a subgenre of hip-hop which utilizes triplets in vocal delivery (spurring the famous Snoop Dogg video in which he mocks that style). The use of lasers evokes a sense of space and sci-fi fantasy, both of which are fitting since Lex Luger’s work has been described as “air rattling, lawn-sprinkler-ish percussion with ominous synthesized orchestration.” And the ascending feeling is created with a filter sweep, a production technique that “sweeps” through a specific range of frequencies from low to high. It is used often in trap music, specifically in risers (a transition technique that increases the value of a certain parameter in anticipation for a drop or chorus). The riser approach is Lex Luger’s confidence that whatever comes next after the drop will exceed expectation and anticipation.

And boy, does it drop.

Lex Luger’s tag lasts just 2.67 seconds. And in those 2.67 seconds, he has referenced his background, speciality, style, and skill. On top of that, he holds the audience to a sense of anticipation, and delivers it as Rick Ross storms into his verse, guns lasers blazing.

-

The growing artistry and appreciation for producer tags has manifested itself in more than a producer tag remix from TikTok user @macaronipenis. Producer tags have been a watermark for producers to lay claim over property: a sonic pat on the back. But they have evolved into a motif and mood-setter for what is to come, beginning from the first second of the track.

In many ways, they signify a shift into a more concise form of storytelling in music production. Musicians are conscious of the luxury of time more than ever before. They understand that listeners might not have the attention span to listen to the ebb and flow of a whole track.

The way to move forward and above the rest is a killer producer tag. Very much like a teaser in your favorite vlogger’s newest upload, the producer tag hooks the audience in; even if the audience chooses to let go of the track, the producer tag will have made an impact.

Graphic designer Saul Bass, who revolutionized the use of film title sequences and worked on films such as “Goodfellas,” “Psycho,” “Spartacus,” and “North by Northwest,” had this to say in a conversation with Herbert Yager in 1977:

“I had felt for some time that audience involvement with a film should begin with its first frame. Until then, titles had tended to be lists of dull credits, mostly ignored, endured, or used as popcorn time. There seemed to be a real opportunity to use titles in a new way — to actually create a climate for the story that was about to unfold.”

So the next time we hear a producer tag that successfully creates that climate for the track to come, I guess we owe it to the producer to “listen to this track, bitch.” Thanks, Drumma Boy.

Garreth Chan is the multimedia editor of Postscript Magazine. He is a transdisciplinary artist from Hong Kong who focuses on the intersection of sound, text, and video. He holds a BA in Music and Sociology from NYU Abu Dhabi.

Garreth worked at a film company as a film colorist and audio engineer before deciding to explore freelancing. His work in film and theater has premiered in Amman, New York, London, Hong Kong, Abu Dhabi, and Budapest, among others.

He is most interested in notions of silence and the mundane.

Artwork by Garreth Chan