Process: A Mentee’s Experience in Warehouse421 x Gulf Photo Plus Artistic Development Program

I applied to the Warehouse 421 x Gulf Photo Plus Image-based Mentorship Program while I was a student in my last semester at New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD) in February 2020. At the time, I was developing my visual arts thesis, where I was looking at various facets of my identity: nationality, gender, religion, ancestry, and language. I started giving words—tokenization, ostracization, othering—to experiences I did not know how to articulate before. Despite seeming like I have absolute privileges as an Emirati, there are other aspects of my identity that marginalize me; to outsiders this marginalization is invisible because Emiratis are presented as a homogenous group. While my Emiratiness was always questioned in my predominately Emirati private school, at NYUAD, an international university in Abu Dhabi, I became the Emirati—the hyper privileged, yet oppressed Muslim woman. In my early meetings with my thesis mentor, Laura Schneider, she asked me if I wanted to represent; she was referring to Olivia Gude’s postmodern principle representin’: “the strategy of locating one’s artistic voice within one’s own personal history and culture of origin,” from her paper, “ In Search of a 21st Century Art Education.” Representin’ became the core of my art practice: a refusal to be a single check mark that fails to personify my multilayered identity.

“Despite seeming like I have absolute privileges as an Emirati, there are other aspects of my identity that marginalize me; to outsiders this marginalization is invisible because Emiratis are presented as a homogenous group. ”

This mentorship program—in partnership with Gulf Photo Plus, a center of photography based in Alserkal Avenue, an emerging art district in Dubai, and Warehouse421, an art and design center housed in Mina Zayed dedicated to cultivating critical discourse through support of UAE-based and regional creative practitioners—had one objective: for its participants to produce an image-based project documenting Mina Zayed, a non-residential commercial neighborhood and deep-water port undergoing redevelopment. The program’s pedagogical structure would guide participants from mentorship to exhibition. Initially I felt I wouldn’t be able to participate; I would have to submit (1) my college economics thesis (2) my college visual arts thesis and an exhibition, and (3) a series of photographs on Mina Zayed, all within May 2020, and I felt I simply didn’t have the capacity. Nonetheless, I wrote and submitted the application with doubt. Then when I heard back, all positive, I thought well, damn.

Ten months later, We Dance Asynchronously on the Same Stage, the series I developed through the program, became the site where the experiences I had started defining in my college thesis took form. I unfolded the complexities of my multiple identities by telling idiosyncratic personal stories paired with each of my 13 photographs. For instance, my analysis of language and ancestry in my thesis comes up in my photograph You can’t sit with us, where I elaborate on a school dynamic where my Arabic dialect and ancestry became a source of contention in some relationships. These stories then became a relatable universal story of partial education, domestic labor, patriarchy, womanhood, and childhood innocence. To do this, I drove my family to Mina Zayed, many, many times, like they used to drive me when I was younger. I chose to bring my family in because they were the people I had access to during the pandemic and because I always experienced Mina with my family. Mina is very much intertwined in the Emirati fabric. I was on a mission to continue to complicate the othering narrative regarding UAE nationals that the larger public often overlooks.

***

“I wished I had enrolled in a journalism class in college because I did not know how to navigate this conversation, to ask for a story, to tell a truth: how does an objective truth in a personal narrative that I am not a part of even look like? ”

As a program, we met in person on two Saturdays in February 2020. In our first meeting we were instructed to step out into Mina Zayed, find a person working there, engage and return with their story and one photograph. This experience conveyed the importance of engaging with Mina, but it also left me uneasy. I first spoke with a truck driver, whose name I cannot recall now, who was carrying medical supplies to Mussafah in a long, long truck. Leaving my introversion behind, I approached him. He was taking a break from driving, and I was hesitant to take up his free time. Time, that because of our unequal footing, he would give me even if he did not desire to. Our different cultural navigation of Mina became obvious when I started listing landmarks—co-op, ace—in an attempt to locate Warehouse421 to explain the project I was making the photograph for. It soon became clear to me that Mina was not a place he was familiar with, he was only passing. What is your story? is a loaded question that can be only answered over time and in small chunks. In an ephemeral community like that of the truck driver’s, the truth would always be fleeting. I wished I had enrolled in a journalism class in college because I did not know how to navigate this conversation, to ask for a story, to tell a truth: how does an objective truth in a personal narrative that I am not a part of even look like?

Our third meeting in March got pushed, when we still thought that we might recover from the coronavirus within three weeks. We didn’t view this halt as COVID-19 yet; in fact the terminology around it was only starting to shift from epidemic to pandemic. This odd turn of events shifted the program’s original schedule. In May, I submitted my university theses, and I graduated virtually with degrees in Economics and Visual Arts. Finally in September, the program recommenced. We met in-person again. When I think about the original schedule now, I see that if things had continued normally, I’m sure I would have produced a completely different body of work. I shifted from being a student to a fresh graduate in a pandemic with ample time to reflect—reflections worth three A5 notebooks—and my relationship with my fellow artists became as cordial as a relationship dragged through a pandemic can be.

Introductions were remade, although I already felt a sense of familiarity among the group, as well as with Mina Zayed. I had walked its grids, visited its markets. I no longer felt like my fellow artists were strangers, maybe because we had multiple conversations in person and maybe because I knew a lot more about their lives through Instagram. Because I am based in Abu Dhabi, I spent many days visiting Mina on research trips, sometimes alone and sometimes with friends. I did this in March too, pre-pandemic. I was most drawn to the area of the warehouses that started evacuating in 2012 and became infatuated with it. When I invited friends to join me, we always spent time among the flamboyance of these spaces. Their colors are the colors of my childhood, bright and daring. I was interested in their visual typology, in the emptiness and quiet of an area in the process of demolition. The streets reminded me of my childhood memories of Abu Dhabi—no traffic lights, no roundabouts, areas dedicated for play. I enjoyed the solitude and felt safe and welcomed.

Flamboyant warehouses

Image courtesy of Lena Kassicieh

Early iteration of photograph ‘Hustle and Bubbles’

Still loyal to self-portraiture, which was the initial idea I applied with, I began remaking some of my childhood memories in Mina Zayed for my work. But the result felt contrived; I was literally placing myself in my memories—if in my memory I was in a car, I placed myself in a car, and so on. There was a lack of freshness, of evolution even, and I was hesitant to show these photos at the next critique session.

The photographs I made among the warehouses were more visually interesting because they possessed a preexisting story—a calendar from 1999, cryptic letters spray painted on a metal door, greenery emerging in the midst of a rubble. I only needed to take a photograph instead of to make a photograph. In hindsight, I should have solely focused on the photographs of my childhood memories during critique. Critique is a safe space that is meant to propel development further. I would have benefited more from showing the idea I wanted to work with, even if the execution wasn’t stellar—it was my first iteration after all, but I felt cautious in showing what I thought was my worser work.

In and around the warehouses

Some artists in our program changed direction after the lockdown hiatus. The pandemic was still rolling and although we met in person, we were still practicing caution. The delay of the program and pandemic not only changed the direction and approach of my work, but everyone else’s too. Lara, who in an early iteration engaged with the community in the plant souq now worked among the dhows, proposing an environmental approach. Augustine who previously worked in the fruit and vegetable market, switched to the truck driver community, shifting his work from still life to documentary.

“I didn’t know what it meant for me, a woman, to visit these spaces with my abaya and visible Emirati-ness. ”

Meanwhile, between my research trips, I told myself that I should also visit the plant souq, the fruit and vegetable market, and the new cafes, and talk to the vendors and salesmen about their experiences working in Mina and about possible feelings of impending change—Mina Zayed’s supposed ‘glow-up’— which could potentially displace its inhabitants. I even dreamt about photographing the markets, but in my waking hours I couldn’t stand the image of my awkward, anxious self being stared or called at in these very male spaces that make up Mina. I didn’t know what it meant for me, a woman, to visit these spaces with my abaya and visible Emirati-ness. My abaya, my loose black fabric, marker of Islamic modesty, symbol of Emirati solidarity, a garment of Emiratiness stitched for the “privileged.” It is a respected attire, yielding respect for its inhabitant. The abaya is a shield when I walk down an Abu Dhabi street. It communicates to men to keep their distance and to avert their gaze. It protects my crevices and curves from objectification. It is a loud garment because what screams louder than a smack of black like that?

“My interactions would have been superficial; I did not want to tell a shallow story”

Although the UAE is a welfare state, different Emirates navigate different statuses of wealth and different Emirati families navigate different social classes. My Emirati-ness puts me on the top of the social structure, albeit untruthfully. I did not know how to make sense of the power dynamic between me and Mina’s inhabitants. Mine of a woman—researcher, photographer, Emirati —and that of the subject—male, merchant, South Asian or Arab or Farsi. Every identifier came with a loaded connotation, so I did not know how to stand amidst the discomfort radiating from both parties, tolerate it, and communicate in a language not native to either of us and lose much in translation. I realized my interactions would never be collaborative, a mutual exchange where both parties would gain something. I could not tell a story of a South Asian man, a multilayered intricate story of migration intertwined with homeland corruption, a religious feud, and a discriminatory caste system. Systems that I only started to understand after engaging with literature and art, in February and March of this year, respectively, reading A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry, historical fiction set during the 1975 Emergency in India, and experiencing I FEEL LIKE A FISH, a work detailing Jaisingh Nageswaran’s personal experience coming from the Dalit caste, the lowest caste known as the “untouchables” in India. My interactions would have been superficial; I did not want to tell a shallow story. I couldn't manage to resolve these knotty, complex dilemmas; thus, I did not end up having the conversations I quite literally dreamt of having.

“Brownness in the context of Emiratiness is a discourse yet to unfold. ”

The story of a brown man is a story I could narrate—this story would be that of my father, of my family. Brownness here would not carry the racial and political connotations embedded in Euro-US-centric terminology. Brown is a color we, Emiratis, also carry in our own way. It is rooted in our maritime trade history with South Asia; it is rooted in our borrowed words—saylan (سيلان) Ceylon, Seeda (سيده) straight. Brownness in the context of Emiratiness is a discourse yet to unfold.

During the Mina trips, there was also a lingering fear that I would be regarded as a government representative—a fear of safety and censorship that Mazna Almazrouei, an Emirati street photographer in our program, came up against too. I asked her to elaborate on this: “I think for me being mistaken for a government representative only lasted the first few minutes as I always chatted with the groups to explain who I am and what Warehouse421 is.” The community of cricket players she photographed were a community of men that visited Mina from mainland Abu Dhabi for its expansive empty streets, they “were a mix of different economic and social backgrounds, some were engineers, HR managers, accountants, taxi drivers etc.” Almazrouei elaborates that there was always an English speaker among the group, giving her access to the rest. COVID-19, not language, was the barrier she faced. “The biggest impediment to be honest was the fear of repercussions because of the COVID-19 restrictions. I didn't know how to get past this; their fears were justified.”

“The biggest impediment to be honest was the fear of repercussions because of the COVID-19 restrictions. I didn’t know how to get past this; their fears were justified.”

Mazna Almazrouei’s “Mina Zayed Repurposed”

Image courtesy of Mohamed Somji

“If an outsider is not given access from an insider they will always be an outsider. ”

Emiratis are not photographed in the mainstream because we are private creatures: private because in our communities reputation is a currency, private in fear of al-'ayn, the evil eye. The discourse around us is simplistic, and coming from NYUAD I knew the consequences—I would always be a token, oppressed when I wear a black abaya, yet privileged and wealthy because of my nationality. I wanted to channel these stereotypical, often contrasting views and complicate the Emirati narrative by showing my experience growing up in the UAE. I asked, what does it mean for an Emirati to navigate Emirati society? And I invited my viewer into my exploration: the outsider who does not know and the insider who shares a different lived experience. Nonetheless, a regular Emirati family does not want to be in the public eye. If an outsider is not given access from an insider they will always be an outsider. They could live in the UAE for longer than my lifetime and still not begin to fathom the “Emirati” experience.

الحاج حسن مكي

Great grandfather in his shop in Deira

Mina Zayed is an important place to complicate this narrative because it has already become a discursive site for discussions and manifestations of narrative erasure, which come with globalization and gentrification. Mina Zayed functions similarly to Bur Dubai, where my great-grandparents once lived in a house overlooking the creek, when Dubai was still an independent trucial state. There, my great-grandfather ran a medical supply store in Deira; he took an abra, a traditional wooden boat, each morning to reach his store on the opposite side of the creek. It is a place that my parents played around as children and then visited as adults. Mina is a place my generation often forgets when thinking of miscellaneous items to buy like chairs or a fireplace, choosing instead to online shop. Mina is the way markets existed before the wealth of my nation. It is a place rooted with history and I grieve its loss through rapid redevelopment because it has been intertwined in my family’s history for four generations. The next generation will not know it as it was. This story rings all too familiar with the gentrification of the Old Souq, where tourists now buy overpriced souvenirs. This is a loss my family actively feels. Now when we want to buy fabric or saffron, we drive to Dubai to Deira.

“Mina is the way markets existed before the wealth of my nation. It is a place rooted with history and I grieve its loss through rapid redevelopment because it has been intertwined in my family’s history for four generations. The next generation will not know it as it was.”

***

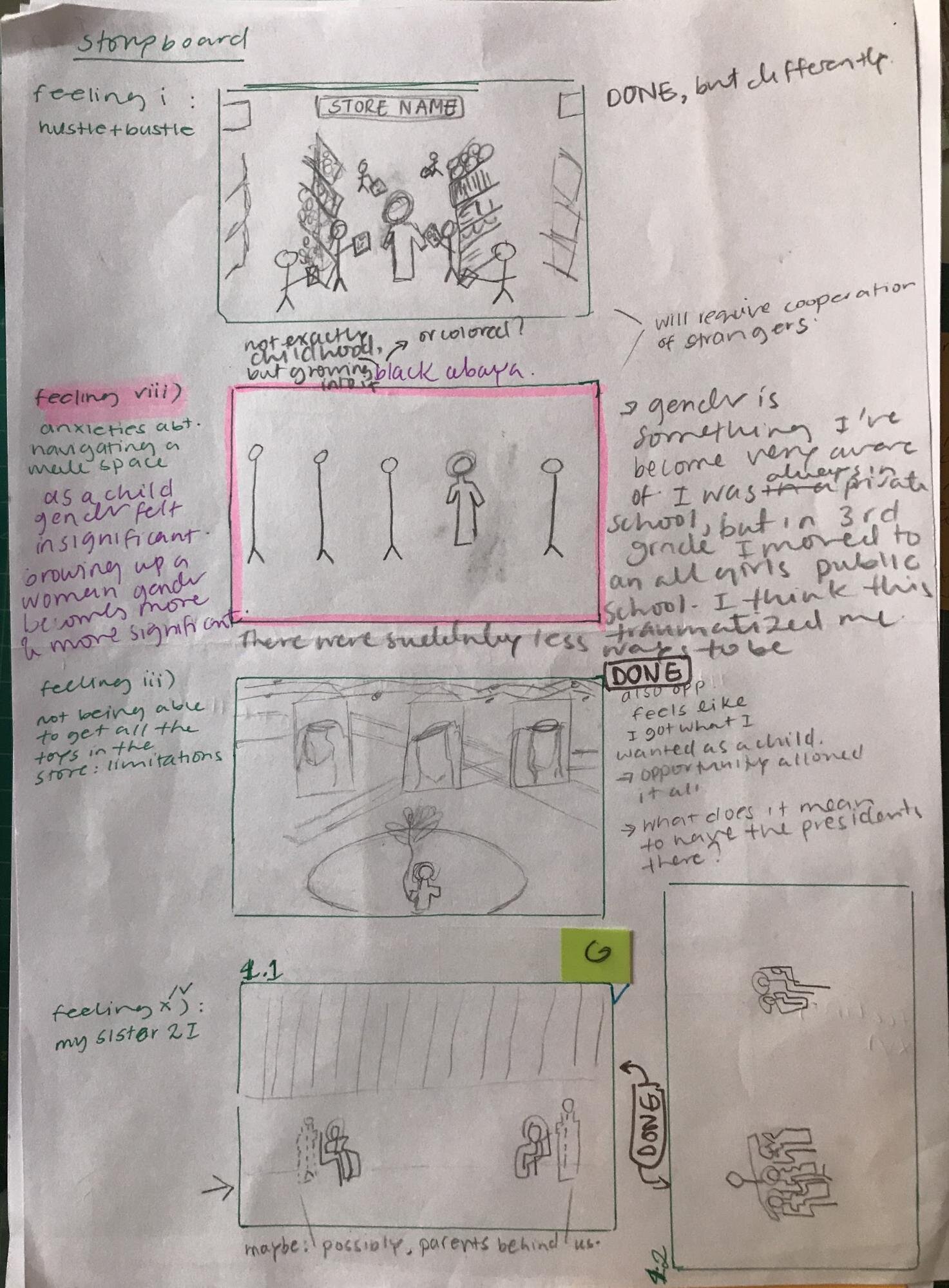

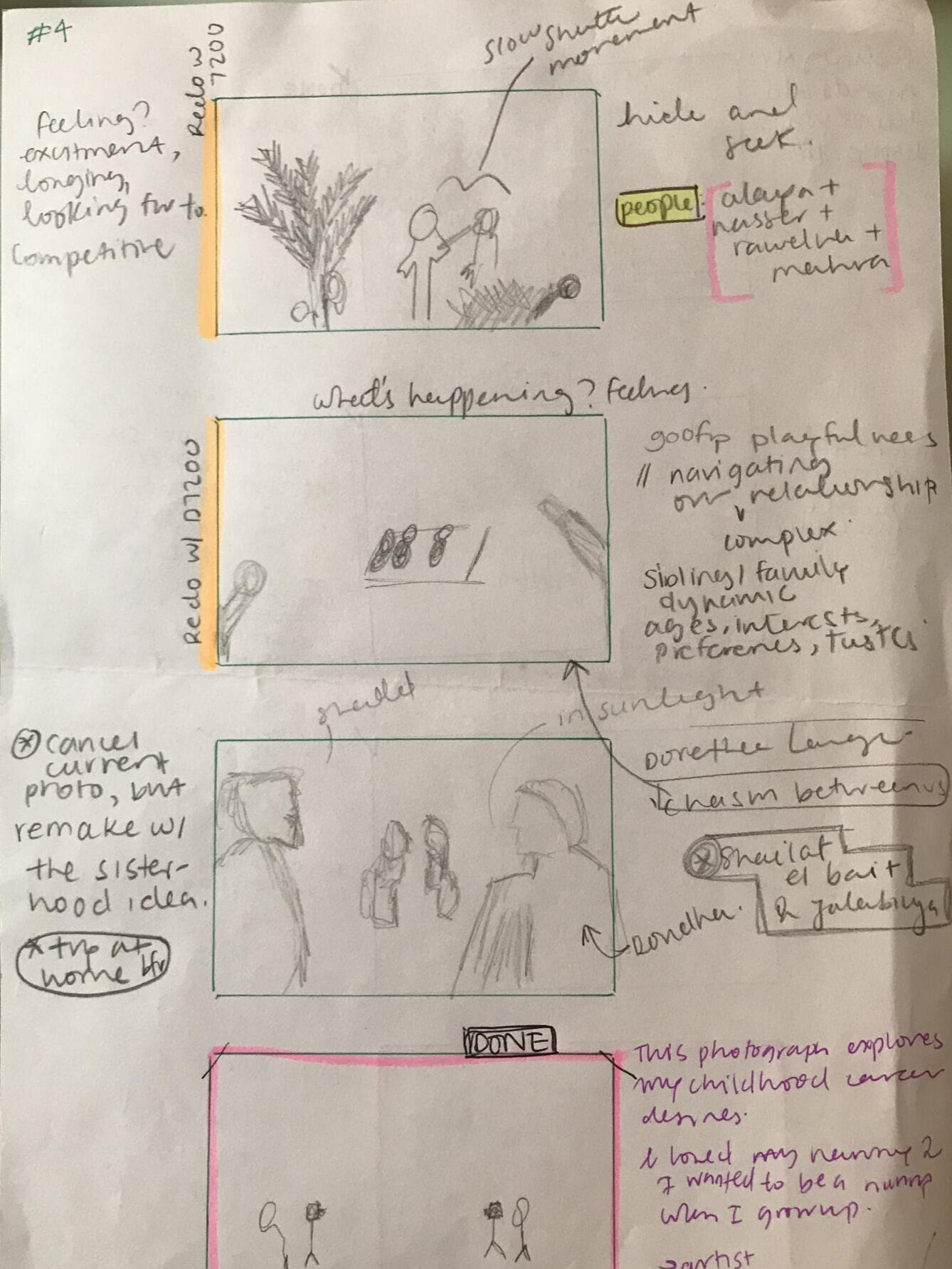

I started to develop my storyboarding master document two weeks after a group critique. I wrote down all my past and present feelings, ideas, and beliefs associated with both Mina Zayed and my childhood, translated them into visual sketches, and located them in the warehouse area. This area became a stage in which I directed my family members and friends to be photographed. Gradually, each sketch was transformed into a photograph; I called the first draft Childhood Compilations Recalibrated. The title referred to certain psychology papers I was reading which focused on childhood amnesia and the malleability of memories. It also referenced my own process of writing down memories, feelings, and beliefs and then visualizing them.

Storyboard master document

On my long list from my storyboarding master document were childhood beliefs like: “wanting to die because children go to heaven. Desire to go to heaven. Obsession.” Memories: “I wanted half my hair to fall off so I can manage it. I used to pray to Allah to give me thin hair.” Ties between past and present: “Hustle and bustle of vegetable and fruit market. As a woman now, this translates to avoidance. I try to avoid the attention of being called at by every seller in every stall. It feels overwhelming and it sometimes feels like harassment.”

Archival photograph

The childhood belief became the photograph Alatfal ydkhloun aljanna, and the hustle and bustle became the photograph Hustle and Bubbles. While developing the former, I thought about the location of a demolished warehouse I visited on an earlier trip. I wanted the soon-to-be demolished buildings to be in my background; they would represent death as they would soon fall. The title of the photograph is transliterated because the thought that children go to heaven only lived in Arabic. I wore a green abaya in an early iteration of this photograph, but I later decided that I would wear a black abaya in all the photographs containing childhood ideas or beliefs. The black abaya would represent my childhood because it is the first garment that is presented to a girl when she hits puberty. I elaborate on this in the text accompanying An Impression of a Conventional Family: “At first, the abaya feels strange, restricting the clumsy and uncoordinated strides of a child, exacerbating the awkwardness of puberty. The colored abayas represent a stage after adolescence where women take back agency over their bodies, experience, and selfhood. Yet, my mother does not wear a colored abaya. She belongs to the first generation of girls who grew up seeing their elders wear a black abaya. Like me, it was imposed on her. The garment evolved in her generation like it does in mine.”

Early iterations of Alatfal ydkhloun aljanna

Earlier in January 2020, I worked as a projection designer using photographs of my family from my thesis exhibition to supplement projection for Al Raheel | Departure— a bilingual poetic play that premiered at The Arts Center. The script, written by playwright, poet and performer, Reem Almenhali, told a story of a girl’s transition from childhood to womanhood. It was the first time I saw a work and thought they are talking about the nuances of our collective Emirati story, of what it means to be a girl, then a woman. I did not actively think about the play while developing my work, but the play also never left me. It represented an experience I lived through my culture, the same culture I was discussing in my works. I revisited Almenhali’s beautiful lines: الطفولُة لا تنضُب على دفعات بل تموُت مرًة واحدة and I wondered how did my childhood die? I did not think it died at once. I thought of the poem that started in the eighth scene with, “morning melts from mourning eyes.” I recited this poem in the shower, in the car, with friends who also watched the show. I was in conversation with Almenhali, a young Emirati artist, like me, while developing We Dance Asynchronously on the Same Stage. The text from An Impression of a Conventional Family, quoted above, alone could have been part of an analysis discussing the abaya’s role in Al Raheel | Departure.

Al Raheel | Departure

Image Courtesy of Waleed Shah

Notes from November critique

Carrying out feedback, I began using a Nikon D7200 borrowed from a family member, a “big daddy camera”, as Maryam, one of the artists, called it. I used a new tripod to handle its mass. I asked each of my siblings to buy me photography-related gifts for my birthday—the tripod came from one of them, and artists' books of Latoya Ruby Frazier and Cindy Sherman from the other two. These books helped me conceptualize my work theoretically. Frazier and Sherman’s works enabled my understanding of both “the personal is political” and staged photography, respectively.

In Frazier’s series, The Notion of Family, she photographs herself and her family in their home in the town of Braddock, Pennsylvania. She tells a personal narrative as a mixed-race woman in the margins of environmental racism, chronic employment, redlining, and white flight. She uses the postmodern principle of representin’ and thus tells a politically charged personal narrative.

From “The Notion of Family”

By Latoya Ruby Frazier

Sherman, in her series Untitled Film Stills, stages herself as a woman in films she spent her childhood watching. Her work perhaps more directly informed the decisions I was making regarding the presence of my family in my photographs. When I read “I didn’t want to title the photographs because it would spoil the ambiguity,” I thought, my titles would add to the intrigue. At the time, I could not understand why artists spent years creating a body of work and then crassly leaving them Untitled. Sherman did not want to give the photo away, but I felt I needed to give a lot away. The art-world she navigated was different than the one I am in now. Furthermore, her rationale aided my understanding of neutral expressions: “What I didn’t want were pictures showing strong emotion. [...] but what I was interested in was when they were almost expressionless.” I would balance giving away my titles, by not giving away my expressions, asking the viewer to work for meaning.

Notes from Albaik’s workshop

I also decided to write more text to aid the reading of each photograph, to give context and access—let's call them contemplations. I first started writing the stories I told in critique, after attending Mays Albaik’s talk in November 2020 through The Fundamentals series offered by Gulf Photo Plus in partnership with Goethe-Institut. The talk reminded me of generative practices shared with me in my visual arts capstone seminar. This practice allows an artist to get out an idea by exhausting it. These iterations sometimes serve as first drafts, like Jennifer Bartlett’s In the Garden (1980-83), and sometimes become the artwork itself, like Richard Serra’s Verblist (1967–68). After that, I was on a roll: writing editing writing writing editing asking-for-feedback editing writing. These stories were extensions and expansions of the long list I had made earlier in my process.

Questions that came up regarding the contemplations were: (1) were they needed at all? (2) if they are needed, how to present them? Mohamed Somji, photographer, curator and director at Gulf Photo Plus, and our mentor in the program, really pushed me to present my text. Somji affirmed that photographs can be strong, but they can only do so much. Different advisors tugged in different directions; some strongly believed the contemplations must live alongside the photographs, while others rejected this idea. Finding my own voice among their voices was challenging.

“Photographs can be strong, but they can only do so much. ”

I paint finding my voice as a challenge, but living it was a large daily spoon of doubt. I sometimes dreamt about my day conversations. Did the feedback I got truly align with my own vision? Who is right? I could not hear myself. Hearing myself was important because I needed to make sure that the feedback I executed aligned with my vision. I reached out to Schneider as she knew me and my work and had seen my thesis evolve over time. A mentor is like a professional parent; a mentor guides you, supports you, and desires for you to succeed. She asserted that the text must find a way to live in the exhibition space because the contemplations are personal stories and a casual visitor will not be able to pick up all the symbols and references I allude to. Finally, I was liberated, unstuck, and I could continue to develop.

The second question of developing the text was that of displaying it. The options I was considering were: audio recording, traditional black text printed on a white sheet, vinyl, QR codes, and a journal-equse personal approach. Somji favored a more personal approach for my work and recommended that I use the walls. This made sense as writing on walls is a mark of both ownership and disillusionment and those fit the themes I present in my series. Writing on the walls was also the option that would allow me the most time to refine the contemplations. I wrote the contemplations in English, the language of my education. Some titles I could only think about in Arabic, so I transliterated them. I thought the ratio of Arabic to English was representative of my education and usage of language in my personal life.

I knew that when you put one work next to another they start to communicate: what is the story I want to get across? I kept forgetting why I decided to have one photograph next to the other, so I started writing my thoughts on sticky notes and invited my sisters to share their own curatorial opinions. This quickly became heated. I found that it was much easier to find my voice in the setting of my family, maybe because we spent our whole lifetimes agreeing and disagreeing.

Curation station

“I knew that when you put one work next to another they start to communicate: what is the story I want to get across?”

As my project developed, my original title no longer fit. Somji suggested I come up with something poetic like Alec Soth’s I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating. I brainstormed two pages of titles before We Dance Asynchronously on the Same Stage came to me. This title referred to adolescence, the transition from childhood to womanhood, the taboo-ness of dancing, and the different hierarchies and structures that exist within the UAE that can be witnessed through Mina Zayed.

I had 13 final photographs. Thirteen is a prime, odd number and oddness comes up in some of my photographs which dictate my family dynamics: five siblings, seven family members. I wanted to embody this discomfort. Thirteen is an untraditional number to present work and cannot be placed in a grid. It is a single unit up from the twelve photographs that are traditionally asked for in portfolio submissions.

In January 2021, installation began. I went to Warehouse421 to arrange my photographs, discuss my final installation sketch, and translate it to the physical space. The week before the opening I spent three days in the gallery, writing writing writing on the wall. I went to three different stores 30 minutes away from my house just to find the right marker to write with. I didn’t have an exact vision for the look of the text, but I knew what I did not want—very bold strokes. I was lucky a security guard named Ahmed had additional markers for me to try and one of them, a Muji two-sided pen, somehow worked like magic. I called the store and reserved ten markers in fear that the one I had would run out of ink halfway through my writing. I ended up only buying four because ten felt excessive, a decision made in panic. In the end, I only needed to use three.

Installation Sketch

On the first Saturday of February 2021, Mina Zayed: Reflections on Past Futures opened. My mom suggested we go see it after the noon prayer and then have a celebratory lunch. I enjoyed going to the opening with my family so much. It was a significant visit because all my trips to Mina, all the commutes, all the in-person meetings I had attended during the pandemic had amounted to something they could physically witness. In the evening, I went to the gallery again to meet up with the entire group. It was much busier than in the afternoon, and I felt admittedly strange seeing people spend time with my work, reading the paragraphs I had mulled over for so long and the photographs I had scurried around my tripod to make.

We Dance Asynchronously on the Same Stage

Image courtesy of Warehouse421

It was my first exhibition—from ideas to execution to installation—as an emerging artist outside an academic backdrop. I’m new to being an artist and new to the UAE art scene. Before this program, I had never branched out of the NYUAD bubble. This mentorship program served as a stepping stone for me, from academia to the local art scene. Through it, I had also witnessed the creative process of ten other local artists and had the privilege to be mentored by a different set of established creatives. And Mina Mina Mina, when do we say goodbye?

Before leaving the gallery on opening night I said to my peers: I hope we can meet again and maybe photograph another area together one day. Lena brought up Dragon Mart, which was brilliant. I had been part of communities like this before, those that meet for a short period of time for a specific purpose and then disintegrate. I had witnessed how the Whatsapp groups slowly died. So when it all ended, I felt a strange early regret. I wondered, as humans are such fickle creatures: what of my life now?

“Mina Mina Mina, when do we say goodbye? ”

“Mina Zayed: Reflections on Past Futures'' is on view at Warehouse421 until June 13, 2021. Watch Artist Talks: Mina Zayed: Reflections on Past Futures to learn more about the processes of participants Fatema Al Fardan, Lateefa Almazroeei, Mazna Almazrouei, and Catherine Donaldson.