Paula Rego's Delightful Violence

The Pain and Wonder of Childhood in Paula Rego’s Peter Pan Illustrations

Underneath a sky of milky stars and a doubled moon, Paula Rego imagines a mermaid drowning Wendy; the beloved “little mother” who was first written by J.M. Barrie in 1904 and then appropriated by Disney in 1953. Wendy half-floats, her body sprawled and still visible through a transparent black sea. She is not resisting the violence being enacted on her, and the mermaid doesn’t seem to be using much force. If Wendy is not dead already, she has accepted her looming death with a sad kind of nobility. This scene never occurs in the original novel. By situating a drowning inside a beloved and well-known children’s tale, Paula Rego reminds the viewer of an uncomfortable truth: childhood is not a landscape free from exploitation or violence. Rego’s Peter Pan illustrations are an exploration of the danger of childhood: a danger that is present in every adaptation of this text, even if it is forgotten or ignored. Rego makes explicit the trauma already lurking in this story, but she also manages to maintain the magic of Neverland, an element of this series that is often forgotten by scholars of her work. Fairy tales like Peter Pan do not create idealized, safe places for children that Rego is simply destroying by bringing in danger from the “outside” world; fairy tales have always been fraught with a danger that Rego brings to the forefront.

Academic Jack Zipes argues that Rego’s images “suggest that the world is discombobulated, and that childhood is a period of abuse and danger for children.” The mermaid lagoon is not free from the dangers that adults face, and neither is Wendy. The mermaid is larger and more powerful than her: she has two strong tails, a broad muscular back and rippling shoulders. Wendy, by comparison, is limp and lanky, only half the size of the mermaid, and is being pushed down into a black sea with nobody in sight to rescue her. Zipes calls this image of the mermaid drowning Wendy “brutal,” and in her monograph, Paula Rego, Fiona Bradley refers to this mermaid as having a “savage determination,” to kill Wendy. Critic Rosenthal argues that “Wendy for once is a helpless child rather than a solid nurturing female… Rego’s version of a siren of the deep is about as unalluring as she could be.” Yet all three critics neglect to address the calm beauty of the image, the nuances of the violence being enacted and how the characters are reacting to it.

At first glance and partially because of the title, we know the mermaid is drowning Wendy. She is undoubtedly being pushed down into water by a threatening figure. So we expect to see something brutal or savage. But Rego subverts that expectation. There is no splashing, no struggle, no fear. The sky creates a starry backdrop that looks sublime and peaceful rather than sinister. The mermaid is strong, but there is no anger on her face, her expression rather oscillates between sadness and grim determination. Her mouth could be firmly closed with a concentrated brow, or her mouth is open and grimacing with sad, upturned eyebrows, expressing regret or worry. It depends on how the viewer sees the image. If Wendy was cropped out, the mermaid could merely be doing manual labour, or massaging a lover, based on her posture and expression.

Wendy is not fighting for her life, either because she is already dead or because she has no desire to fight. Her left arm rests against the mermaid’s tail, and her right arm floats upwards, her hand awkwardly bent out of the water. Her face and ears seem to be out of the water, leading to the question of why the mermaid isn’t pushing her down by the head. Wendy seems oddly reliant on her murderer to stay afloat. Her legs are spread in a way that resembles some of the women in Rego’s “Untitled. The Abortion Pastels” series such as the one below.

"Untitled," Paula Rego

Wendy is vulnerable specifically as a young girl. The more the viewer looks at the image of her and the mermaid, the more maternal the mermaid seems. She transforms into a mother who is simultaneously pushing her daughter down and keeping her alive. She doesn’t seem to want to kill Wendy -- she easily could if she wanted to -- and if Wendy is already dead then the question becomes: why is the mermaid still holding her up?

Behind the two figures, the pole on Marooners’ rock is the only sign of a male presence, where the pirates will later tie Tiger Lily in an attempt to murder her. This conveniently phallic object looms over both women like a flagpole, looking down on them. Not only is Rego pointing out the existence of trauma in a child’s world through this drowning, she is depicting its nuances. Sometimes it is beloved, trusted figures who enact violence on children. Sometimes one kind of violence is the only way to spare a child from another worse kind. The image of abuse can also be painted as hauntingly beautiful; throughout the Peter Pan illustrations, however, Rego shows that pain and beauty can coexist in one moment.

Jack Zipes argues that art made in reaction to fairy tales serves to undo their imagined utopias. Artists such as Rego use the fairy tale “to pierce artificial illusions that make it difficult for people to comprehend what is happening to them.” But I disagree with the assumption that fairy tales seek to create a utopia, or “soothe an anxious mind,” as Zipes calls it. In fact, much of what is explicit in Rego’s mermaid image is implicit in both Barrie’s and Disney’s versions. In Barrie’s novel, Wendy and the mermaids do not have a good relationship-- they present a threat to her, “she never had a civil word from them… they utter strange wailing cries; but the lagoon is dangerous for mortals then.”

In the play version of this story, also by Barrie, Peter warns, “They are such cruel creatures, Wendy, that they try to pull boys and girls like you into the water and drown them.” Their threat to Wendy is distant under Peter’s protection, but it still lurks. This fairy tale specifically warns against groups of women who live together outside of a patriarchal structure. Wendy is better off being a “young mother” than risking the unknown amongst the mermaids. The Disney adaptation picks up on this fear of autonomous women and makes it more explicit by heightening the mermaids’ threat: they grab Wendy’s clothes, try to pull her down, and splash her. When Peter tells them to stop, one mermaid declares, “we were only trying to drown her.” Rego takes this fear of autonomous women, embedded in the original text and the film, and uses it to show how women fear each other and hold each other down.

In her article “Paula Rego’s Sabotage of Tradition: ‘Visions’ of Femininity,” academic Gabriela Macedo points out how Rego violates the invisible boundaries that demarcate what can and cannot be criticised: “Rego’s career has been devoted to crossing into forbidden territories (fascism, Catholicism, patriarchy); while her rewriting of national memory aims at exorcising fear, as well as exposing guilt and hypocrisy… makes it at the very least difficult not to see.” I would extend her argument to include childhood and fairy tales as other forbidden territories that Rego violates. Childhood is treated like something sacred, and adults expect children to behave in certain ways because of their own imaginations of what it means to be a child. Fiona Bradley argues, “Rego’s subjects refuse to conform to what might be expected of them, courting ambiguity so that their situations remain mobile… tender embraces are easily confused with violent struggle.” It would be nice to imagine childhood as a period of simplicity and tenderness, but Rego uses ambiguity to violate this imagined utopia that is dreamed up in the minds of adults. In the Peter Pan series, Rego makes explicit what already anxiously lurks in fairy tales. And she violates tacit understandings that we all collectively imagine childhood as something pure, and free from trauma.

In Rego’s illustration “Tiger Lily Tied to Marooners Rock,” a young girl in a loose white dress calmly allows herself to be bound to a rock that will soon be deep underwater. Her body is relaxed and her eyes are closed, but we know that she is awake because she squats against the rock rather than sprawls against it. Her captor is an unsmiling male figure who is emerging from the strange black shape around them, presumably Marooners Rock itself. Both he and the rock are black: parts of his body are disappearing into it, and he appears more statuesque than the other characters, creating the impression that he is a part of the rock coming to life, or has been carved out of it for the purpose of binding captives.

Two boys watch Tiger Lily’s demise with curiosity, and two mermaids do nothing to come to her aid. Similar to “Mermaid Drowning Wendy,” the violence of this image is doubtless. Tiger Lily is trapped on a rock where she will eventually die, and nobody seems interested in rescuing her, even though they easily could. Yet Rego once again subverts expectations about how violence is supposed to look, and what it can mean.

Tiger Lily, like Wendy, does nothing to resist the violence being enacted on her. Her captor has no true legs to chase her with, and he is just about to finish tying her up. So how did he force her into that position in the first place? If someone else brought her there, then why isn’t he tying her himself, and making sure that she doesn’t escape? Tiger Lily looks neither scared nor sad about her future death, and her expression remains peaceful, perhaps even joyful. If she wanted to escape, she could have easily wriggled away from the animate rock-man. So it seems that she has decided to allow this violence to happen. Maybe she even sought it out herself; maybe she enjoys it. This intersection between pleasure and pain is not supposed to occur in children’s stories because it is usually seen as disturbing or sexual. Seeing a young girl getting pleasure from violence is a violation of our collective imagination of childhood. Macedo writes about Rego’s violation of Catholicism and patriarchy, arguing that, “Whether ‘the mater’ confronts directly gender or games of power, social and political hierarchies, it always ‘defies the pain’ and gives the viewer no solace, but… a tantalizing sense of pleasure and threat.” Tiger Lily, as a child, experiences both pleasure and threat in a violent world. She is playing a game that we usually think children are exempt from.

In the background of this illustration, at a strangely small scale, a silhouetted male figure points a rifle at a mermaid tail, which is diving into the piece of land he is standing on, or into the water behind it. The presence of the mermaids to the right of the picture makes it clear that the tail is a mermaid and not a very large fish, so it is definitely a female being hunted. The image is easy to miss, but it presents a foil to Tiger Lily’s behaviour. She may have sought out the violence she is experiencing, but the mermaid runs away from it.The viewer then returns to wondering why Tiger Lily is so complicit in her own trauma.

It is possible that she desires this pain and enjoys it, but that does not make her passive or powerless. Rosenthal argues that in this image, “Rego depicts her [Tiger Lily] as just another helpless female, which is doubtless legitimate considering her plight. One would, however, have enjoyed seeing what Rego might have made of this feisty Redskin woman warrior… had she chosen to depict her in one of her more militant moments.” Rosenthal doesn’t acknowledge the power of Tiger Lily’s choice in the face of violence. Instead of being afraid, she embraces trauma and appropriates it for her own use; Rego could have illustrated this female warrior in a fight, but she chose to depict a more nuanced situation where Tiger Lily remains somewhere between freedom and constraint, despite literal bonds. She is not “just another helpless female.” Her decision to find pleasure in trauma is an act of resistance, an alternative to militancy, and a representation of how some women and girls find freedom under immense patriarchal constraint.

Tiger Lily and Wendy are both young girls who are threatened by violence. It is a threat that is implicit in Barrie’s fairy tale and exists in the lives of real children. It would be wonderful to imagine that childhood is a utopia free from trauma, but fairy tales have always hinted at the vulnerability of children and the horrors they face. Rego draws out the danger that lurks in Neverland: where female monsters drown children, men tie little girls to poles, boys shoot girls out of the sky, and a grown man is obsessed with capturing and killing a young boy. Rego’s work complicates and amplifies the anguish of childhood, whilst maintaining another seemingly paradoxical truth, which is that fairy tales, childhood and trauma are often also beautiful.

References

Rosenthal, T.G. Paula Rego: The Complete Graphic Works. London: Thames and Hudson. 2012.

Grey, Tobias. “Paula Rego’s Dark Fairy Tales,” Blouin Art Info.

Macedo, Gabriela. “Paula Rego’s Sabotage of Tradition: ‘Visions’ of Femininity,” University of Wisconsin Press.

Peter Pan (film). Walt Disney. 1953.

Barrie, J.M. Peter Pan, Or The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up. The Folio Society. 1992.

Barrie, J.M. Peter Pan. Aladdin Paperbacks. 2003.

Zipes, Jack, The Irresistible Fairy Tale. Princeton University Press. 2012.

Bradley, Fiona, Paula Rego. Tate Publishing. 2002.

Miller, Sandra, “Paula Rego’s Nursery Rhymes,” Print Quarterly Publications. 1991.

Rosenthal, T.G. “On Art and Essays” Andrews UK. 2014.

Fortnum, Rebecca, Contemporary British Women Artists: In Their Own Words. Taurus & Co. 2006.

Mermaid Drowning Wendy, Paula Rego (1992).

Tiger Lily Tied to Marooners Rock, Paula Rego (1992).

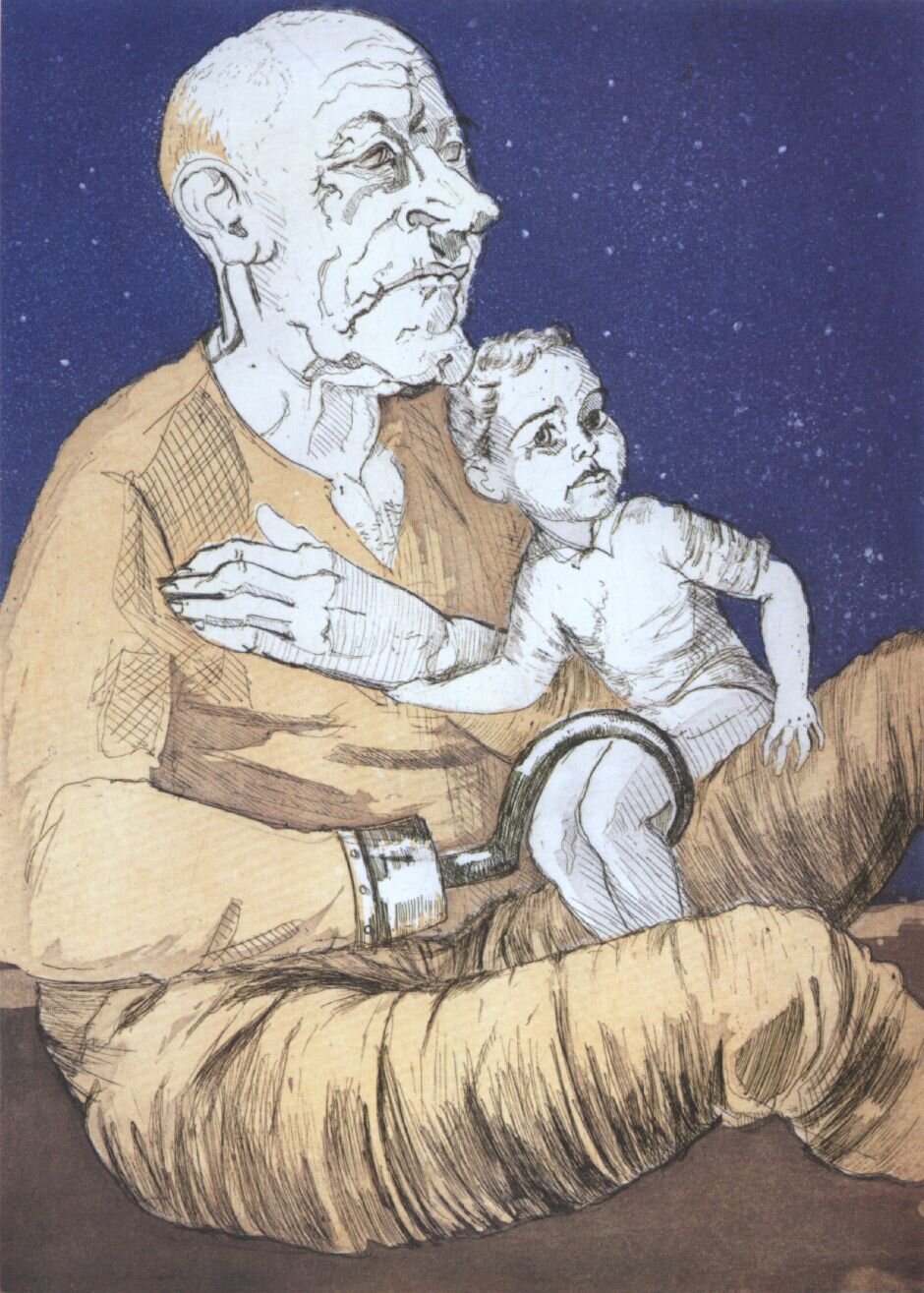

Cover art by Paula Rego "Captain Hook and a Lost Boy"