When I Get Home: Solange's Cartography

The map of Houston, Texas looks like a star break on a windshield. When the glass has been pierced by a sharp point, leaving a spiral of injury. Perhaps, due to a stone. A bullet. On the fourth track of Solange Knowles' new album When I Get Home, there are gunshots. You could almost miss it; the clocking of the gun, interspersed with its firing, is so effortlessly melded into the melody. Much like news of recent deaths often sink beneath the frantic newness of news.

Unlike this album's predecessor, the magnificent A Seat at the Table, When I Get Home is less construction than map, a route along the roots of a steady, reflective driver: Solange. She is credited as a writer on every track. But it's important to acknowledge that this is not her story – "I realize how much wider, figuratively and literally, my work could be if I took myself away as subject" – but stories, plural, that are narrated by her. Here, Solange creates conceptual cartography: of her Southern roots, of black empowerment, black women, and their intersections with their own personal and collective histories, and their love, spirituality, emotions, and power.

There are numerous, predominantly black, collaborators on this album, all in various capacities, ranging from features, production to writing. The lineup includes such names as Tyler, the Creator, The Dream, Metro Boomin', Pharrell, The Dream, Cassie, Earl Sweatshirt, Gucci Mane, Raphael Saadiq, Abra, and Playboi Carti. The most interesting "collaborations" however are the interludes featuring a variety of black female voices, including the artist's. One interlude is titled "Can I Hold the Mic" which choppily samples a video of crunk group Crime Mob's female rappers Diamond and Princess faux-interviewing each other – "Uh, bitch, can I hold the mic?" This leads into a spoken-word section by Solange herself:

"I can't be a singular expression of myself, there's too many parts, too many spaces, too many manifestations, too many lines, too many curves, too many troubles, too many journeys, too many mountains, too many rivers, so many – "

This instability of identity, of the failure to contain and distill Solange's specific experience as a black woman, perhaps explains her decision to produce a sonic map instead, one that stops focusing on an inconstant, non-singular self, but instead actually charts out the terrain of self, exploring those many "mountains" and "rivers" that make up her emotional-historical-cultural-political being and existence. Part of this is paying a nod to those that came before her; on S McGregor, Solange includes a recording of Houston-born women Debbie Allen and Phylicia Rashad reciting a poem by their prolific mother Vivian Ayers: "I boarded a train/Kissed all goodbye." The track comes very early in the album, right after the repetitive, one-liner opener Things I Imagined, as if to foreshadow the movement, both literal and figurative, and the endings or goodbyes that Solange has undertaken to realize her visions. When she asks Can I Hold the Mic, it is not to profess a personal declaration, not to ask to be accepted as one self, or embodiment of self, not even to ask for a seat at the table, but instead, to ask us, to invite the world, along with her as she moves and retraces the "lines" and "curves" of her map of being.

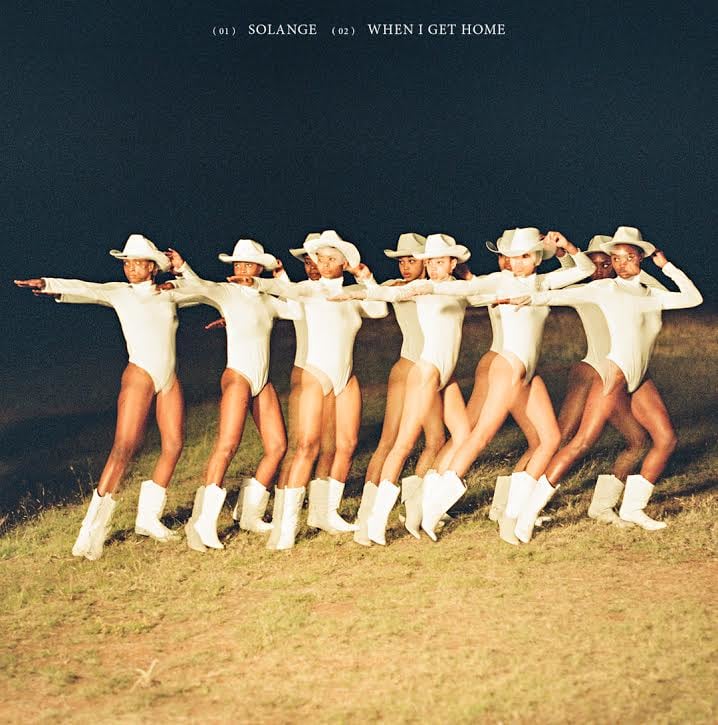

The cartography begins, as Solange's life itself did, in Texas. If the map of Houston, her city, is a fractured spiral, then it revolves around its blackness. Houston Third Ward, where Solange grew up, is known for its black community. It was a civil rights epicenter in the sixties and had the first nonprofit hospital for black patients in the thick of the Jim Crow era. A profile by The New York Times Style Magazine states that "[Solange's] output is infused by a fundamental orientation – culturally, politically, psychically – to blackness." And this is her central spin throughout. Solange frequently incorporates the chopped n screwed hip-hop style in her core jazz and hip-hop music, inflecting her work with black musical forms that specifically nod to her city. A song celebrating black and brown things – "Black baes, black days"' – is named Almeda, an area in south-west Houston. S McGregor is for S MacGregor Way, where the aforementioned sisters Debbie Allen and Phylicia Rashad grew up. Way to the Show's "candy paint" lyric pays homage to Houston's staple slab scene, where cars are painted to look candy-coated. Meanwhile, Beltway refers to the road looping around Houston, which, on the tracklist, is cleverly followed by Exit Scott, a real exit off the Beltway 8 in southern Houston. In visuals for the album, Solange prominently features a ranch, with horses and dancers in modern cowboy outfits. “Hundreds and hundreds of people every weekend are getting on horses and trail-riding from Texas to Louisiana,” Solange told Billboard. “It’s a part of black history you don’t hear about.” It is clear the geography serves as scaffolding for the album, propping up every vision executed by the artist.

It is in Exit Scott (interlude) where Solange showcases the poetry of Pat Parker, a lesbian black woman from Houston itself. The poem is about love. In the intermission, We Deal With the Freak'n, Solange includes audio of Alexyss Tylor from her show Sperm Power 2: "We are not only sexual beings, we are the walking embodiment of god consciousness", a track that is preceded by the Gucci Mane feature My Skin My Logo, which contains an outro resembling sexual climax. Solange explores the nuances and spaces of black love and sexuality through the lens of actual black women, from Parker to Tylor, each exercising agency and ownership of their sexual and romantic narratives.

These also expand to the topic of spirituality. In 'Nothing Without Intention', Solange cites the black beauty blogger Goddess Lula Belle's video on Florida water, an item Solange carried with her to the Met Gala in 2018. Florida water is a unisex cologne made with alcohol and essential oils, used for purification, spells and spiritual cleansing. It is also a prominent part of Afro-American spiritual culture. In the track Almeda, there is a lyric that declares "Black faith still can't be washed away/ Not even in that Florida water." Solange simultaneously celebrates black spirituality while asserting the resilience and strength of black faith as transcending every hope symbolized by any spiritual object; black faith is stronger than any spell. On top of that, the refrain "nothing without intention" is a call to the listener, perhaps, to examine Solange's full cartography as painstakingly and thoroughly mapped. As in an exquisitely made poem, every element is cherry-picked for maximum fruition. But invoking intention is also a rallying cry to her community, to the black community, to the black women before, with, and after her, to know and find and search for their beauty and being.

The title My Skin My Logo is a reclamation of the idea of using blackness as a brand (re: blaxploitation) and exacting power over it. Binz offers a similar celebration of wealth in this lens – "Dollars never come on CP time/ Wish I could wake up on CP time" – where CP time is 'colored people time', a historically derogatory phrase used to imply that black people were lazy and tardy. Solange basks in her wealth and power, spinning the narrative that has historically held people like her down for their success.

Pride, having pride in an inconstant state of self and history, and comfort with this pride, are key factors of When I Get Home. A lyric in My Skin My Logo states to "blackberry the masses", a gorgeous play on words that recalls the saying "The darker the berry, the sweeter the juice", which elevates dark skin. At the same time, there is the darker double meaning in "bury the masses." It's an invocation, to and for the black community, that is sweet-bitter; like the Houston cars lacquered to look like candy, this lyric draws on both the pain and beauty of blackness in a political world, invoking, above all, hope, the sweetness and necessity of it.

In the same NYT magazine profile mentioned earlier, Solange recalls being afraid of the Holy Ghost as a young girl at church. This fear, not just of that imaginary phantom, but a wide-encompassing fear, found in the pit of every artist's chest, manifests in the intro track Things I Imagined. Solange ends this song with the lyric "Takin' on the lie." By the time we reach the last track, Solange no longer imagines but declares: I'm a Witness. This song transforms the old lyric into "Takin' on the light." There is a movement here between imagination and vision, fear and realization, off-track to grounded, intention to execution. In When I Get Home, a title itself implying a road and destination tied to self, Solange sketches for us this journey, maps out the paths that have led her to this exact moment as both artist and woman and black being. How strange, how searching, and how beautiful it all is.

Map of Houston, Texas