A Feminist Icon? The Historical Leadership of Coco Chanel

What defines a leader? For the benefit of this piece, I define a leader as an individual who is capable of swaying or manipulating the beliefs of their followers/constituency, towards executing a particular set of visions or actions. In other words, leaders simply change beliefs – beliefs being defined as what other people think. Whether they are politicians, musicians, CEOs, hedge fund managers, or in the context of this article, fashion designers, leaders use a variety of methods to visualize and realize one or several goals by influencing a cohort into helping them do so.

Here, I will be discussing and analysing the leadership of Coco Chanel. Coco Chanel was a fashion designer and entrepreneur who started her own couture business selling clothes, hats and perfumes in France, following the end of World War I. Today, there are 310 Chanel boutiques operating worldwide. Additionally, the company is ranked 87 in the world on Forbes’ list of most valuable brands and is valued at $7.3 billion, generating an annual revenue of $5.2 billion, as of May 2017. To be more specific, I will be examining how and why Chanel’s unconventional, quasi-masculine designs and brand successfully reshaped society’s beliefs on the functions and paradigms of both fashion and femininity in the 1920-30s, leading to Chanel’s immense corporate success. Ultimately, using Coco Chanel’s early career as a case study, I intend to assert that her ability to change Western, and eventually global, ideals of women’s fashion was a demonstration of her powerful, even feminist, leadership style and legacy.

Gabrielle ‘Coco’ Chanel came from a poor, rough background, born in 1883 to a laundry-woman mother and street vendor father. When Chanel was only twelve years old, her mother died of tuberculosis, after which her father left her and her siblings to stay at a religious orphanage in central France. There, Chanel learned how to sew and eventually left to work as a seamstress and cabaret singer on the side. Chanel was considered quite beautiful but even more witty and flirtatious. She received the name “Coco” from the French cavalry officers that frequented the cabaret she sang at, because one of the most popular songs she sang was “Ko Ko Ri Ko”. Another more scandalous possibility is that the name was a reference to cocotte, the French word for a prostitute. During a working night at the cabaret, when Chanel was 25, she met former cavalry officer Ètienne Balsan, a wealthy heir to a textile company. Amid the mingling of the singers and cavalry officers, Balsan became captivated by Chanel’s wit and ambition and soon made her his mistress; she even moved into his chateau in Compiegne and began to live a very lavish and leisurely lifestyle where she could socialize with members of higher social echelons.

Chanel soon grew idle amid this new rich life. As a result, Balsan decided to financially back Chanel and helped her open a hat and dress shop in Paris, the epicenter of French society’s arts and culture. In 1909, having become an established milliner with Balsan’s help, Chanel met and fell in love with a British businessman, Arthur “Boy” Capel, one of Balsan’s close friends who visited Balsan’s home in the summers. The passionate affair lasted nine years, during which Capel provided Chanel with the capital to open two additional boutiques in the rich, aristocratic French towns of Deauville and Biarritz.

Before delving into the greater specifics of the rise of Chanel’s business, it is worth noting how the two lovers in Chanel’s life at this point in time, namely Balsan and Capel, impacted her design aesthetic and business, and thus, her success as a leader. Due to her experience of poverty and her distaste for the excessively flamboyant, ruffled, hyper-feminine clothing that women were expected to wear in that era after World War I, Chanel rebelled by often sporting menswear, which was a more affordable and comfortable option. She frequently borrowed garments from her lovers’ closets. The effect of this can be seen, evidently, in even her earliest clothing designs. Chanel’s clothes displayed more unconventional, ‘masculine’ colours such as blacks and nudes, and used extremely sparse decoration, if any at all. Chanel also particularly became fascinated with the jersey fabric – typically used to make male underwear and hosiery – that she first encountered in Capel’s closet. She came to use this traditionally masculine and cheaper fabric, along with others such as tweed, prominently in her clothing designs throughout her career.

Chanel’s clothing was also atypically looser and freer than what standard dictated; during the post-World War I period, societal conventions dictated that woman wear uncomfortable and constrictive tight corsets, flouncy dresses, large elaborate hats and ruffles. Women were expected to present themselves as pretty objects, plump and feminine for the return of soldiers from the war. Chanel’s designs subverted these standards. She used her designs as her rhetoric or propaganda for the ‘myth’ she was selling – the ‘myth’ of a more confident, liberated woman, free from corsets and convention. She developed the Chanel suit for women, with a much looser fit and more accommodating neckline. She introduced, shockingly, pantsuits as an option for females as well as males. She dropped the waists and shortened the lengths of her skirts and dresses, and crafted smaller, plainer hats, much like the men’s. And of course, she created the iconic little black dress, a plain black, almost shapeless, loose dress for women, completely opposite in style to the then-favoured dress style of long, heavy, ruffled skirts cinched tight and piled with colourful feathers, ribbons and beads.

So how did Chanel actually change the beliefs of French society, leading it to adapt and even embrace her radical new designs in a social atmosphere that revered extreme femininity and the objectification of women?

During the post-WWI era, many women were seeking to build careers in a male-dominated workplace. During the war, women had joined the workforce as nurses, or in civil service and factories while the men were away. A lot of these jobs involved high physical activity and heavy commuting. Increased employment of women sparked a growing desire amongst women to break free from the confines of excessively rigid and conservative societal expectations that demanded they should stay in the home and behave and dress in certain ways. Chanel noticed and tapped into this unspoken desire – one she felt herself as an independent female entrepreneur coming from a peasant background – and offered women the opportunity to express and simply be themselves more freely through the realm of fashion. She was a visionary. Her naturally rebellious, slightly shocking and highly individualistic nature exemplified the emerging streak amongst women: to defy societal standards that demanded they remain rigidly and uniformly feminine, fulfilling a male post-war fantasy. Perhaps one could say Chanel was lucky that this aspect of her nature conveniently aligned with this growing feeling of dissension amongst women at the time. But it is Chanel’s ability to recognize this lucky coincidence and use it as a tool to leverage her fashion business and sell her ‘myth’ that was more important in her making as a leader.

Chanel’s designs of fluid jersey suits and dresses were considerably more practical and allowed for easier movement in a working environment. Her clothes were durable, did not require a servant’s help in putting them on and were created using cheap and easily accessible fabrics in a time when the war had caused a shortage of other materials. Hence, Chanel’s modification of the construction of women’s clothing to fit more comfortably and affordably was welcomed by women who were striving to be part of and remain with ease in the workplace and thus, become more independent and liberated. Even though the incredibly unconventional colours, shapes and fabrics introduced by Chanel were not immediately welcomed due to their unusualness, they gradually and consistently gained increased popularity because of this unspoken need amongst women at the time to be freer and break from the norm.

Therefore, this becomes an example of how Chanel used her designs as a way of challenging and eventually changing society’s perceptions of what the paradigms of fashion and femininity should be. Her clothing enabled women to perceive themselves and thus, all of society to perceive and approach the female gender in a more progressive way, allowing women to both look and feel more confident and liberated in a society that tended to repress them. In a nutshell, Chanel not only wanted women to free themselves of physical corsets but also of mental ones. This reflects on not only her incredible creativity as an artist, but also her acute sense of vision and shrewd intelligence in terms of successfully shaping her business according to the social atmosphere and then using that power to re-shape that social atmosphere towards the better.

Another piece of evidence that can be used to support the claim that Chanel successfully changed social attitudes towards fashion is through the fashion trends that we know now characterised the ‘flapper’ era of the 1920s and the economic slump of the 1930s Great Depression. The 1920s were considered a time of celebration in the wake of the end of a war; American jazz culture had just been imported to Europe. People engaged in more dancing, drinking and casual sex; consumerism was on the rise. Women were working outside of the home more and challenging traditional societal roles that regarded them as weak and powerless, as aforementioned. Women also wanted to be considered as men's social equals and were faced with the difficult realization of the larger goals of feminism: individuality, full political participation, economic independence, and sex rights. Chanel tapped into this surge in women’s desires to embrace particularly their individuality with her designs and general ideology of style. Her straight, loose, waist-less dresses, shorter skirts, complete lack of tight corsets and the short, bobbed hairstyle that she popularized and donned herself, were considered markers of the modern, flapper girl, the symbol of this freer era. This shows just how successful the designer was in swaying the beliefs and perceptions of femininity and fashion in European society at the time. Even in the Great Depression, Chanel’s business continued to boom. Her use of cheap, practical fabrics in an economically-challenged period was appealing to the masses. At the same time, the sombre colour palette of her designs, largely consisting of blacks, greys, navy’s and nudes, reflected the gloomier, graver social mood of the 1930s, a time of intense economic hardship following the Wall Street Crash in America, with people naturally gravitating towards more serious hues.

Chanel’s targeting of and socializing with a particular set of clientele was another crucial factor contributing to the success of her leadership or ability to revolutionize the fashion world at the time. The location of her boutiques in areas with high numbers of upper-class aristocrats and celebrities, such as Paris, Biarritz and Deauville, was strategic; the more they wore her clothes there, and got photographed in them in the media, the more popular Chanel’s brand and style would become, gaining the veneer of idealized high-class taste and status. Additionally, Chanel was offered money to dress high-profile movie starlets, who, once seen in her clothes, propelled her popularity to even greater heights. Actress Marilyn Monroe was famously quoted as saying: “What do I wear in bed? Why, Chanel No. 5, of course”, referring to Chanel’s perfume, released in 1926. Following this statement, Chanel’s sales skyrocketed. In fact, she was so successful she was able to pay back Capel’s loans to her in full, just four years after he helped set her up in business. Moreover, the iconic poster of actress Audrey Hepburn, clad in a snug little black dress, holding a cigarette lighter and coolly gazing out of the frame from the 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany’s, was probably one of the most picturesque images produced by Hollywood. This poster was a landmark one because it firmly established Coco Chanel’s little black dress as an exceptionally desirable item.

Chanel’s strategy worked; media exposure was instrumental in popularizing her brand and vision. "The woman who hasn't at least one Chanel is hopelessly out of fashion … This season the name Chanel is on the lips of every buyer" was published in Harper’s Bazaar, a major fashion magazine, as early as 1915. In 1926, the American edition of Vogue magazine published an image of a Chanel little black dress with long sleeves, and predicted that such a simple yet chic design would become a virtual uniform for women of taste, famously comparing its basic lines to the ubiquitous and no less widely accessible Ford automobile. Chanel’s rising popularity landed her in increasingly exclusive social circles, often through the combination of help from Balsan and Capel’s social connections and networking, and the success of her boutiques in rich, aristocratic hotspots like Biarritz. Through frequent parties and events that she could attend on the basis of her connections to Balsan and Capel and her newly-established reputation as a high-profile designer, Chanel befriended Stravinsky, Picasso and other members of Paris' exclusive art clique. She designed costumes for Russian ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev and French filmmaker Jean Cocteau. Her visibility with such high-profile figures helped attach the label of ‘luxury’ to her brand and therefore, her ‘myth’ that she was selling as a leader. Chanel’s brand epitomized the idea that if one wore her designs, one could be both comfortable and impressively chic. It was an attractive myth that the rapid growth of Chanel’s business proved was well bought into by European society. Chanel succeeded in changing the beliefs surrounding fashion and how one could be fashionable; she established herself as a leader of the fashion world.

Chanel pioneered the myth of the more liberated woman, in a society that thrived on confining and constricting women, through her designs and fashion brand – and she succeeded. She changed beliefs and thus, she became a leader. She sold her myth through tenacious dedication to executing her vision, a vision that cleverly tapped into the unspoken collective desire of the women in her society to be more free and independent. Once a few women bought into Chanel’s ‘rhetoric’ – her clothes, style, vision of the modern woman – other women too began to rapidly conform to this stylistic display of non-conformity. The media embraced it and Chanel became a symbol of class, comfort and luxury, all incredibly lucrative characteristics. The wide reach of Chanel’s new vision of fashion and femininity changed beliefs about the perceptions of women in society in general and provided fodder for the budding feminist movement. This ability to sway the thoughts of a collective group towards a vision is what makes Chanel a powerful and timeless leader – after all, her business and artistic empire and legacy extends to the present day - still alive and thriving. Chanel herself summed up her leadership style well: “A leader knows the way, shows the way, and goes the way.”

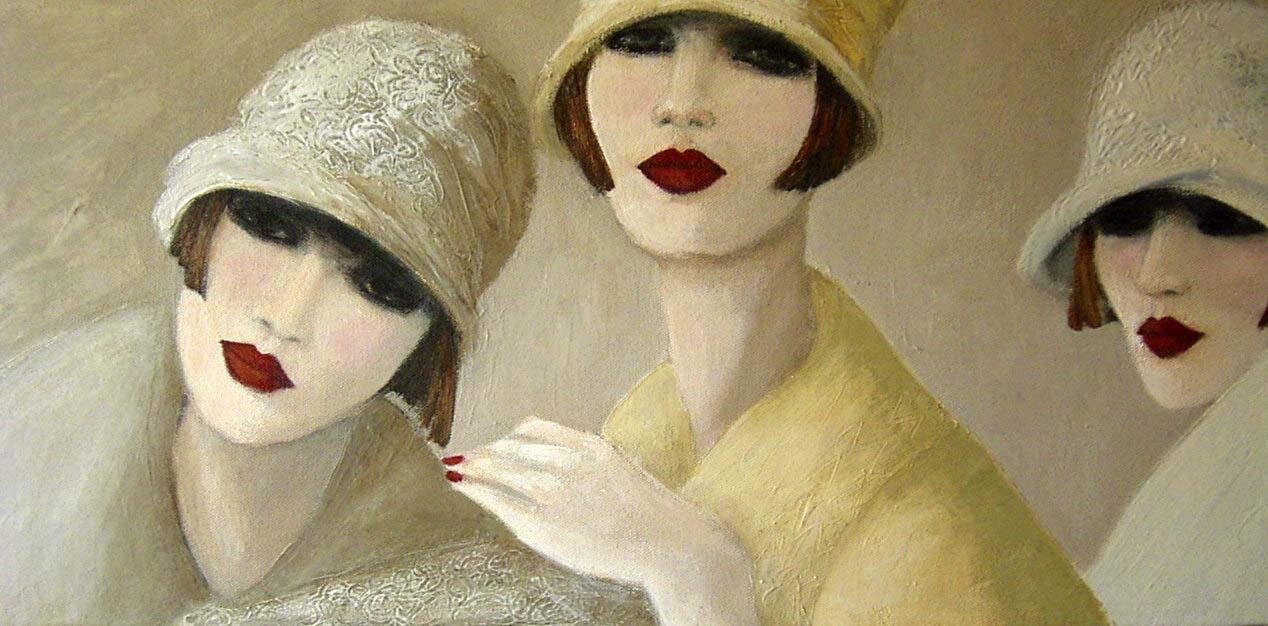

Artwork by Mo Welch

References

“Coco Chanel Biography: The Woman Who Changed The World Of Fashion”. Astrum People. 1 November 2017. Web.

“Coco Chanel..Blog #2”. Women’s and Gender Studies Blog. 11 October 2007. Web.

“Coco Chanel’s Feminist Progress Through Fashion”. Bellatory. 29 August 2017. Web.

“Gabrielle ‘Coco’ Chanel”. Entrepreneur Middle East. Web.

Graj, Simon. “Coco Chanel: Personal Branding Legend”. Forbes. 20 February 2013. Web.

Jones, Barbara. “Coco Chanel (Part One)”. The Enchanted Manor, 19 August 2015. Web.

Latham, Angela J. “Posing a Threat: Flappers, Chorus Girls, and other Brazen Performers of the American 1920s”. Hanover NH: University Press of New England. Print.

Muller-Ramirez, Nina. “Coco Chanel. Her life, lifestyle and fashion”. Grin. 2000. Web.

Pandit, Sharwari. “Of History, Coco and the Little Black Dress”. Critical Twenties. 17 July 2015. Web.

Picardie, Justine. “The Secret Life of Coco Chanel”. Harper’s Bazaar. 11 July 2011. Web.

Sischy, Ingrid. “The Designer Coco Chanel”. Time. 8 June 1998. Web

“The World’s Most Valuable Brands - #87 Chanel”. Forbes. May 2017. Web.

Wollen, Peter. "Cinema/Americanism/the Robot". Indiana University