The Color Blue

Jazz. A single syllable — voluptuous, soft and as biting as a cymbal crash. I’m thinking about this, the punchy, pillowy now-ness of the word — jazz — as my plane descends into JFK Airport. It’s my first trip to America. The veins of Manhattan are splayed out below me, like a bunch of musical staves jumbled together. Scott Fitzgerald comes to mind, the man who made Gatsby and declared the 1920s as the Jazz Age. That was a sad book. A beautiful, sad book. Manhattan glitters on. The lights grow closer; sequins on a flapper’s dress. We land with a thud — crash! Gatsby is shot, Gatsby is dead. Somewhere in his tiny New York apartment, a young trumpet player performs a solo on his balcony. It is beautiful and sad. The former Nigerian slave Olaudah Equiano once wrote of his race that “blue is our favourite colour.” Now when I put on some Coltrane in the subway train, I am underground but I can hear the sky.

***

There’s a woman at the City College of New York who used to teach a class on jazz poetry. You’re probably wondering what that is — so was her ramshackle group of disinterested students on the first day of class. I’ll withhold that information for now, just like she did. Instead, the first thing Emily Raboteau did was put on some Louis Armstrong. A 1954 recording of the song “Tenderly”, a kind of slow New Orleans funeral dirge that, like all the blues, she notes, was both depressing and triumphant at once. The students stir. Feet tap, heads sway, something in them comes alive like a newly-emerged butterfly. You know when you want to leave a song pristine on its own, to not taint it with words or explain away its magic? “Tenderly” is a song like that. I listen to it and watch the yellow cabs drift by on a sunny day in the East Village and Louis’ trumpet seems to speak and think and dream out all the feelings within me. I guess Raboteau felt a similar way. When the song ends, she doesn’t bother dissecting the music but instead reads her class a quote from Ralph Ellison’s book The Invisible Man:

“Sometimes now I listen to Louis while I have my favorite dessert of vanilla ice cream and sloe gin. I pour the red liquid over the white mound, watching it glisten and the vapor rising as Louis bends that military instrument into a beam of lyrical sound. Perhaps I like Louis Armstrong because he’s made poetry out of being invisible… And my own grasp of invisibility aids me to understand his music... Invisibility, let me explain, gives one a slightly different sense of time, you’re never quite on the beat. Sometimes you’re ahead and sometimes behind. Instead of the swift and imperceptible flowing of time, you are aware of its nodes, those points where time stands still or from which it leaps ahead. And you slip into the breaks and look around.”

“That’s what we’re going to do in this class,” Raboteau explains to her students. “Slip into the breaks of what we hear and write about what we see.”

***

Jazz is jaywalking on the streets of New York, caught in a conversation with traffic where one of you must impulsively go silent.

“Jazz is being at a famous art museum and saying, "Wow, isn't that the most beautiful thing you've ever seen?" But, instead of pointing at a painting, you're pointing at a regular old water fountain.”

***

When music and words get married, they have a child and that is poetry. Whenever I write, I’m always thinking about the rhythm, the sonic texture, of what’s coming out on the page. Maybe you’ve noticed that already. The two are forever wedded together in my mind, music and words. Jazz poetry is their honeymoon. Officially, it’s defined as a literary genre where the poetry is necessarily informed by jazz music — the poet responds to and writes about jazz, sometimes even embodies it through the pacing of the words and the choice of structure. “[Jazz poetry] takes the poet out of the bookish, academic world and forces him to compete with ‘acrobats, trained dogs, and Singer’s Midgets,’ as they used to say in the days of vaudeville,” wrote American jazz poet Kenneth Rexroth. In other words, jazz poetry involves mixing up the traditional forms of poetry into an entirely different cocktail of wordplay, just as jazz players take classical structures and stretch them, free them, improvising their way into new sonic and notational realms.

Another definition of jazz poetry is simply the recitation of poetry along with jazz music. However, Rexroth notes that the poem shouldn’t merely be read against music, it should integrate into it. “The voice is integrally wedded to the music and, although it does not sing notes, is treated as another instrument," he wrote in a 1958 essay. In essence, the words and music must be inextricably woven together, both on equal footing. If not, then you’re just listening to poetry over some music, two distinct forms placed on top of each other. If yes, and the marriage occurs, then together the forms successfully fuse into this relatively novel phenomenon of jazz poetry.

***

An old man walks by on a street in Greenwich Village. He has a bad leg so his gait swings. The man taps his cane to a regular beat while his body repeatedly leans in one direction, his head dipping to the side with the rhythm. Synchronization. His little dance-swing-walk matches the beat of “Tenderly” playing in my ear as I look out from a café. New York is grit and glitz but sometimes it is so soft, so unbearably tender.

“New York is grit and glitz but sometimes it is so soft, so unbearably tender.”

***

Let’s go back for a second to Raboteau’s class at City College of New York. On the second day, she hands out the lyrics to another song Louis Armstrong made famous: “(What Did I Do To Be So) Black and Blue,” and the students listen to it . One verse goes:

I’m white inside, it doesn’t help my case

’Cause I can’t hide, what is on my face, oh!

I’m so forlorn, life’s just a thorn,

My heart is torn, why was I born?

What did I do, to be so black and blue?

Many of Raboteau’s students are people of color, immigrants or the children of immigrants. The defeated yet implicitly defiant and controversial lyrics suddenly unlocks their usual silences. The caged bird sings. One student criticizes Armstrong for claiming to be white on the inside in order to somehow validate his own humanity or confirm the inferiority of Blackness. In defence, another points out that the song was written in 1929 when the times were more racist, more segregated. One girl remarks that the times are still segregated. Someone observes that Louis Armstrong didn’t even write the song. Another struggles to articulate the song’s irony — the very Blackness of the singer’s face which he can’t hide and which marks him so visibly is also that which renders him invisible. “This is a mad sad song,” says a boy named Christopher, shaking his head. “It’s not just sad,” somebody disagrees. “He’s asserting himself. He’s saying he’s not a sinner just ’cause he has Black skin. He’s speaking up to the ones who kept him down.”

***

Jazz is that blurry photograph that didn’t come out right and that’s why you hang it up on your wall.

“Jazz is a struggle, like when a handsome white man really wants to open a jazz club, but has to settle for being a very famous and successful musician instead, and then also eventually opening a jazz club.”

***

In the preface to The Jazz Poetry Anthology, editors Sascha Feinstein and Yusef Komunyakaa make a fundamental point about the confluence of race, jazz, and poetics: it is impossible not to address the synthesis of verse and music when attempting to place African-American poetry in its historical and social perspective. A lot of Black poetry has been associated with Black music throughout history, which is what has led to the birth of this sub-genre we call jazz poetry. Jazz poetry, in that case, is ultimately a Black art form at its root, because it is borne from the conglomeration of two originally African American art forms.

***

Droning a drowsy syncopated tune,

Rocking back and forth to a mellow croon,

I heard a Negro play.

Down on Lenox Avenue the other night

By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light

He did a lazy sway . . .

He did a lazy sway . . .

To the tune o’ those Weary Blues.

—from "The Weary Blues" by Langston Hughes

***

Many consider the original founding father of jazz poetry to be Langston Hughes. In the 1920s, Hughes, an African American from Harlem, New York, began to write poetry that reflected the rhythmic patterns of African American oration embedded in the tradition of folk, blues, hymns, and prayers, all of which together formed the vertebrae of jazz music itself. For Hughes, the blues form was indistinguishable from poetry and so he used the jazz aesthetic as a way of talking about culture, race, history, and as a choice — perhaps emblematic of the jazz aesthetic — to be joyful in spite of unjust and harsh conditions, specifically faced by African Americans in a racially segregated United States. With his first nationally recognized, blues-infused poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” Hughes also established a socially conscious jazz poetry form which essentially preserved an ethnic tradition and established a distinctive literary practice common to a unique cultural experience based on the shared identity of African Americans. He felt that jazz poetry could thus be distinctive among the contemporaneous, very white poetic canon. And so when he wrote about jazz, Hughes often incorporated syncopated rhythms, jive language, or looser phrasing to mimic the improvisatory nature of jazz; in other poems, his verse read like the spare, pained lyrics of a blues song. Just like jazz contains the metanarrative of rebelling against traditionally white, Eurological, more structured and homogenized classical music, Hughes’ melding of jazz and poetry could be seen as a counter-response to the dominantly white literary and poetic material circulating at the time. Hughes wanted to create art “of, from, and for Black people”. His jazz poetry not only performed this act of assertive rebellion, just as Armstrong’s “(What Did I Do To Be So) Black and Blue” was an artistic revolt against colorism, but it also created an enduring artistic legacy that extended beyond both Hughes’ lifetime and ethnic boundaries—first with white Americans and then expanding across the globe, including modern Arab poets and musicians, and other various artists of color, later on.

***

just juice

alto sax says to piano

piano keeps flipping

eggs

bacon

juice

this morning I scrambled unscrambled eggs

alto says

— “The Deli” by Anna

Raboteau has noticed that her student Anna is playing with line breaks, creating a see-saw of words like a Harlem stride pianist — down-up-down-up-down-up. The dialogue poem was assigned as a response to Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie’s “My Melancholy Baby”, a bebop number that’s not as immediately accessible or danceable as swing music. When Raboteau asks her how she did it, Anna shyly responds, “Jazz happened to my punctuation.”

***

For the poet Langston Hughes, jazz was a way of life, not merely an enchanting sound. It symbolized the rejection of the desire for assimilation and acceptance by white culture and rejoicing in Black heritage and creativity instead. Hughes was an avid proponent of the blues, a form that comprised the parentage of jazz, and elevated the quotidian troubles of African Americans into art; rather than simply wishing away hardship, blues and jazz stared it in the face and spun something beautiful and thought-provoking out of it. In his 1926 story “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain”, Hughes wrote:

“But jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America; the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile.”

“For the poet Langston Hughes, jazz was a way of life, not merely an enchanting sound. It symbolized the rejection of the desire for assimilation and acceptance by white culture and rejoicing in Black heritage and creativity instead.”

***

My high school history teacher, Mr Hoosain, would sometimes put on old Beatles records or Gil Scott Heron and deviate from the syllabus to talk about The Great Gatsby or his life during the apartheid regime in South Africa. As a young, brown Muslim man forced to live and travel only within ‘colored’ zones, he joined local resistance movements against segregation. One day, he heard one of his colored friends, a resistance fighter, had tragically died from a car bomb planted by the authorities. I looked around then, at my ‘international’, ‘integrated’ classroom, and felt something cold like an ice block inside my chest. Nobody spoke for a while after that.

One day, I told Mr Hoosain I was thinking about studying literature and he did this thing when he got excited, where his eyes bulged and he started bouncing on his toes. He started to lend me a lot of books after that, his Saturday-morning-in-bed favourites, as he called them. “You’ll like this,” he’d say, handing me a red paperback. “It has a lot of music running through it, especially jazz and sixties tracks.” I started making playlists out of the novels, combing through YouTube on school nights. In one book, the music of John Coltrane was described so affectionately, with such intrigue and wonder, that I looked up the song — “In a Sentimental Mood” — and it sounded like the taste of a sweet cherry. With that, I began tottering on this often bizarre, meandering path of jazz.

In Mr Hoosain’s class, we would spend a lot of time straying into the worlds of music and literature — jazz, rap, paperbacks — and having spontaneous, passionate discussions that transcended the cliquey boundaries of high school interaction. “Don’t you see? The Great Gatsby is not about an ill-fated lover. It’s about the Jazz Age, the swing of a giddy generation, the money and optimism and the loss of it. It’s about hope — and the American dream. This dream is false, Fitzgerald is trying to say. It’s an alloyed dream, the furthest from gold you can get,” Mr Hoosain would say, his eyes shining, our eyes shining, all of us replete with new ideas. I would picture a younger version of him, learning the news of the car bomb, his friend, and think of how every people and every nation has a dream, each one equally blue and alloyed.

Last year, Mr Hoosain died from a heart attack. I realized the person who taught me how to unfold the past, would now always belong to the past — and remain there for the immeasurable amount of time that is forever. When I first heard about his death, my initial thought was that I can never go back. I can never go back and talk to him, never thank him for all that he did for me, for all of us, and the words and music he offered me to fill in the coloring lines of my existence. In my mind, a quote from Gatsby resurfaced: You can’t repeat the past. You can’t repeat the past. Now 1 am in a New York diner, I suddenly think of Mr Hoosain again. I tell my friend sitting across from me that I had never really cried for anyone’s death before that. In my head, I remembered how every time John Coltrane or Charlie Parker improvised a ripe, delicious solo, it was never played the same again. But generations of students continue to unfold, inscribing these solos to their memories, hoping to glean some of that same magic themselves.

***

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

—from "Harlem" by Langston Hughes

***

Art is one of the few mediums where people of color can exercise agency and autonomy over the existence and representation of their own culture. And history shows us that jazz was one of the mediums that African Americans used to reclaim and rewrite the Black narrative in America. This began largely with the 1920s Harlem Renaissance, a sociopolitical and artistic movement where Black storytellers began using the emotive power of the arts as a tool to redefine Black identity for newly and increasingly interracial audiences. Langston Hughes was one of the icons of the Harlem Renaissance and a symbol of mixing together two prominent, predominantly Black art forms coming out of there in order to find new ways of reshaping the Black American narrative. Harlem was a hotbed for jazz music at the time, housing major clubs like Minton’s Playhouse where important musicians such as Duke Ellington performed; at the same time, the Harlem Renaissance was also centered in large part on literature because New York was a hub of publishing. These were the ways renaissance was measured at that time — arts and letters.

Jazz and poetry, and later rap, were used to speak to the collective will of African American urban artists to bring the sociopolitical experiences and the struggles of Black urban communities into “white” cultural spaces. In 1961, right in the thick of the Civil Rights Movement, Hughes’ jazz poetry exerted a more pronounced political consciousness. In one of his works, Ask Your Mama, Hughes created powerful images of ghettoisation and the social-racial power relations that have produced and delimited black urban space:

WHITE FOLKS’ RECESSION

IS COLORED FOLKS

DEPRESSION

“Art is one of the few mediums where people of color can exercise agency and autonomy over the existence and representation of their own culture.”

***

To me, jazz is a montage of a dream deferred. A great big dream—yet to come—and always yet—to become ultimately and finally true.

—Langston Hughes

***

On the way to a jazz gig, I am quietly catcalled. No one hears and I don’t say anything. My heart is an irregular tom-tom. We meet our professor at the venue, a place labelled cutting-edge and on the verge of closing. It has a name to match — The Stone. Sounds slightly forbidding, except to those who are up for whatever challenge that’s conjured in this space. Tonight, we are here to watch two experimental trumpet players engage in a sort of sonic combat-slash-love affair. They start to play, or squeal and squeak and seemingly hurl sonic expletives through their instruments; my first reaction is to disengage. Abort mission immediately. Slowly, however, I notice images and scenes rising like vapor from the noisy grit. The gentle susurrations of a kettle; waves and gulls at the seaside; domestic farts, sneezes, and kissing; the anatomy of a traffic jam; a car horn; silence — the silence of sleep, of barely-there breathing, of insomnia, of not knowing what to do; and sporadic moments of coordination, some semblance of harmonies. My mind is electrified. I feel gorged with poetry and words and mental visuals, all from about ninety minutes of pure sound, which on the surface, felt like garbage. Whatever this was — experimental, avant-garde, free — I somehow feel it unscrewed a bolt in my thought-machinery. I often think of music as fantasy and pleasurable escapism, but whatever these performers did was a direct confrontation of life and reality. It is a confrontation, and thus a kind of acceptance, of all of what it is to exist in this world and society — the banal, the beautiful, the getting catcalled in a foreign city.

***

Jazz is the archive section of a new-age hipster’s library, titled “Things That Literally Saved My Life”.

“Jazz is balling up your fist and just punching a keyboard a bunch of times.”

***

As Raboteau’s class progresses, she notices the students’ work becoming more abstract in form, content, and image. Kazu, who struggles with English as a second language, writes a poem about Miles Davis’ eyes, in which she compares his trumpet to “a glass of angry whisky.”

Emanuel writes a poem called “The Length of Thelonious Monk’s Beard Explained”. It’s about the pianist’s invisible, vestigial third and fourth hands.

‘Jazz is the archive section of a new-age hipster’s library, titled “Things That Literally Saved My Life.”’

***

Jazz likes to do the opposite of foreshadowing, which is the proclamation of something that came before — the hint of a previous tune, “quoted”, then turned on its head, made afresh. When you hear a familiar sound reconstructed from an earlier generation, it’s like being given the currency to buy your way into a new tune. A poet, traditional or jazz-influenced, does the same. They live with the contents of the tune and/or subject matter, and from it, and what is found nearby in the world, shape and present it to us in their words. So the music continues in these words, accompanied by the author's response to the chords and notes, the news they hear, and the emotions they feel.

Writing this piece is a work of jazz for me. And here are the specifics of what I am doing. There is “quoting” — which many jazz musicians do with earlier tunes as making jest or paying homage — through the sharing of personal memories and anecdotes, alongside actual historical information on both jazz and poetry. There is “trading” — when jazz musicians engage in a kind of musical dialogue, passing phrases/solos to each other — through responding to the ideas of various scholars, performers, and writers mentioned in this paper. I mix academic syntax with more colloquial language, serious, researched paragraphs with one-liners, small poems with streams of consciousness, facts with opinions. Those asterisk breaks are like cues or bar lines. And there is a playful disjointedness, an element of surprise and disruption, in the structure of what you are reading. Perhaps it feels a bit jarring? A bit disorienting?

Well, good.

***

“Jazz is going "Beep boop beep boop beep boop beep boop" until someone writes an article about you.”

***

Poets have continued to admire and utilize jazz because of improvisation — because of this particularly enduring quality of freshness and they see it as a catalyst for their poems. Because jazz was seen as music of the moment, capable of combining energy and sadness in one primal cry (or mere saxophone solo), it became eminently suited to the Beat Generation and its poets and writers. The Beatniks belonged to a subculture in the 1950s and 60s, comprising artists, writers, musicians, and critics who wanted to rebel against war, capitalism, and bourgeois values, and advocate instead for freedom, spirituality, and sexual liberation. They adopted the name “Beat” because it related to being an outsider in society but also had an optimistic ring, something the writer Jack Kerouac pointed out when he connected beat with "beatific" and "beatitude," meaning a state of utmost happiness and bliss. The double-meaning of the word accurately describes the complex state of being beat, which means that, at the same time, you can be vulnerable and sensitive, rejected from society and teeming with existential despair, and still be wildly enthusiastic about the world, trying to see and describe it in all its diversity, spirituality, and poetic beauty.

It was this quality — that of being an outsider who still retained their optimism through suffering — that the Beat Generation shared with jazz music. After all, the roots of jazz stemmed from the African American struggle, of feeling invisible and downtrodden yet still holding on to hope, a quality we have already seen documented in Hughes’ jazz poetry as well. Consequently, many Beatniks used jazz as both fodder and frameworks for their writing. They sought to bring words closer to music, comparing the howl of the human soul with the deep blowing of a saxophone. Another meaning of beat was like a beat in music or a drumbeat. Jack Kerouac especially was influenced by jazz music and his prose was rich with rhythmical patterns. Sometimes, he deliberately wrote in the style of a saxophonist, with long flowing sentences like an endless saxophone solo or short sentences like razor-sharp little riffs. Kerouac called this style of writing spontaneous prose and there is a clear analogy between his stream of thoughts and the act of improvisation present in jazz.

The combination of jazz and poetry reading was also particularly pioneered in the Beatnik era. Kerouac recorded with the saxophonists Al Cohn and Zoot Sims, while poet Kenneth Patchen played with the Chamber Jazz Sextet. Music was present in the syntax. The Beatnik icon Allen Ginsberg often talked about the influence of saxophonists Lester Young and Charlie Parker on his famous poetry collection "Howl”. The Black writer Leroi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka) was not only influenced by jazz, he was also a jazz critic, spearheading the field of jazz academia and jazz journalism through books like Blues People (1963), where he theorized the impact of the blues and African musical traditions on the development of jazz. Jones was also an enthusiastic attendee of jazz clubs and concerts in various settings, and was continuously coming up with innovative and poetic ways of thinking and writing about jazz. At the same time, the American author John Clellon Holmes produced one of the first and finest jazz novels ever written, with his portrait of the fictive saxophonist Edgar Pool in The Horn (1958).

The idea of Zen and being present in the moment was also central to the philosophy of the Beat Generation and perhaps best expressed poetically in the form of a haiku by Kerouac: "What is Buddhism? / -A crazy little / Bird blub." The bird could be an ordinary bird in nature, but it could also be the saxophonist Charlie "Bird" Parker playing a "blub" on his saxophone, penetrating the silence with the song of his horn.

***

Jazz seeps into words — spelled out words.

Spilled out words. Angry whiskey. Tears.

***

Although the majority of Beatniks were white people who often emulated the African American jazz poetry of Langston Hughes, a handful of Black people also participated in the movement. The Black Beatnik most directly influenced by Hughes was the aforementioned political activist, writer and critic Leroi Jones, now known as Amiri Baraka. Following the popularity of the Beats, Black writers in the 1960s, including Baraka, sought to create art that specifically reflected the urban Black experience, which came to be known as the Black Arts Movement. Baraka, who grew up reading Hughes’ poetry, noted how Hughes’ work engaged directly with the Black community. And so, Baraka was inspired to identify with Hughes as a sort of role model in furthering the goal of creating unique and distinctly Black art forms. According to poet and critic Lorenzo Thomas, Baraka’s poems, such as "Black Art" and "Black Dada Nihilismus," aimed to raise awareness of the struggling African Americans living in deteriorating urban conditions, and the necessity of urban renewal and cultural uplift through both anti-poverty activism and the production of culturally and socially significant poetry.

***

We listen to John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme album in full for the first time in jazz class. Our only obligation is to stay entirely focused on the music. Through its duration, I find myself drifting in and out of some kind of meditative state — one of my old friends would have called this accessing the hyperconscious, while a psychologist with a really long name that I don’t remember might have called it flow.

I am tempted to write poems made out of planets and color. Coltrane plays on.

After the album ends, I do not say anything. I get up and go to the bathroom, look into the mirror and start to cry. I don’t know why I am doing this but the crying is coming from some deep, knotty part of me that I cannot pinpoint. Somewhere in the third movement of the album, it sounded like the saxophone was crying for help. Listen to me. God. Listen to me. Love me. Love me. I cry harder. I know that every human on this planet, for at least one point in their life, has become that saxophone.

***

“Jazz is a great big sea. It washes up all kinds of fish and shells and spume and waves with a steady old beat, or off-beat.”

Jazz isn’t the black key or the white key or the silence; it’s that sharp intake of breath, the force exerted by your fingers, and the involuntary, borderline blissful shutting of the eyes, as you place your hands on the instrument.

***

Baraka, along with other literary giants of the Black Arts Movement such as female poet Gwendolyn Brooks, not only set a precedent in terms of the structure and musicality of spoken word and rap, but also further normalized the use of Black English in the literary world. They highlighted and increased the usage of quotidian African American language and daily Black vernacular within the poetic canon, an important source of inspiration for a group who called themselves the Last Poets. On May 19th 1965, the birthday of civil rights activist Malcolm X, they debuted their new hybrid of Afro-jazz inspired rhythms and performance poetry, which artfully employed repetition, literary devices, and tone manipulation that foreshadowed the emergence of early hip-hop. They also used a lot of improvisation, which eventually led to the development of what is now called ‘freestyling.’

The Last Poets are now known as the godfathers of rap, for they pushed a political narrative bigger than them that was able to capture audiences because of the relatability of their messages, from 125th Street Harlem to the academic elite. The storytelling component of their work also touched upon a collective consciousness that is still very much relevant in hip-hop today.

“Jazz isn’t the black key or the white key or the silence; it’s that sharp intake of breath, the force exerted by your fingers, and the involuntary, borderline blissful shutting of the eyes, as you place your hands on the instrument.

***

True blues ain’t no news, about who’s being abused/for the blues is as old as my stolen soul/I sang the blues when the missionaries came/passing out bibles in Jesus’ name…I sang the backwater blues, the rhythm and blues, gospel blues, saint louis blues, crosstown blues, Chicago blues, Mississippi goddamn blues, the watts blues, the harlem blues…”

—The Last Poets

***

Just as Langston Hughes and Amiri Baraka piloted the development of jazz poetry, the Last Poets, Public Enemy, and other new hip-hop artists started promoting ethnic and communal pride in the African American experience through their music. Hip-hop, now birthed from jazz and jazz poetry, as jazz was once birthed from the blues, became the cultural expression du jour for Black American youth. For instance, in hip-hop artist Grandmaster Flash’s 1982 track “The Message,” there was a nod to Amiri Baraka’s poem “Black Art,” and other early hip-hip artists rapped poems that promoted awareness of a shared cultural experience of living in oppressive urban conditions. Their music highlighted the urban decay and poverty blighting Black communities in the US, and helped restore the vitality and pride of African American culture through the hip-hop art form, just as Hughes made the same call much earlier in the Harlem Renaissance with his jazz poetry.

***

Take all the tubes of paint you own, mix the colours together and you get the colour black. This too, this especially, is jazz.

***

Arab hip-hop artists, such as El General, Deeb, and Syrian rapper Omar Offendum, also took important cues from jazz poetry and the emergence of hip-hop. They saw it as a tool for civil resistance against harsh living conditions; it expressed and depicted the frustration felt by many in the politically tumultuous Arab region. “Rap is poetry at the end of the day…and that is something that Arab culture can definitely associate itself with,” said Offendum in an interview. In another instance, rapper Public Enemy compared hip-hop to CNN, suggesting the art form was important for broadcasting and connecting the socially concerned voices of Black and other minority or oppressed communities. Hence, hip-hop, as a child of jazz poetry, provides an artistic platform to promote solidarity based on shared cultural and ethnic experiences. In an online video, Offendum actually pays homage to the roots of hip-hop by reciting Langston Hughes’s jazz poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” and then he raps the poem in Arabic, which is often regarded as a language of poetry. The rivers of the past that united black culture for Hughes, now provides unity and pride to Arab culture as “The Arab Speaks of Rivers”.

“…hip-hop, as a child of jazz poetry, provides an artistic platform to promote solidarity based on shared cultural and ethnic experiences.”

***

“If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn't matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. The tom-tom cries and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn't matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.”

—Langston Hughes

***

Jazz is when you're tutoring a young musician and you give him a very large textbook called Jazz Information and tell him, "Everything you need to know about jazz is inside this book," and he opens the book, and guess what's inside? A mirror.

***

I walk in the rain. I don’t really know where I’m going but we just passed Little Italy glowing on the left, awash with mist. The two of us are on our way to the next jazz club and then the next, improvising sidewalk strolls, subway routes, conversations about lost loves and past selves. We spread ourselves out on the grids of New York like leaping notes on a stave. It’s ‘round midnight. Something like that. Time flows on without us noticing. We forget it exists. Jazz brims out of basements and bars and boreholes around the city. I will always remember this. I will always remember this like the melancholia of “Mood Indigo” by Duke Ellington. This is our own jazz piece, the blue notes blurring strangers into friends, anxiety into passion, while around us the street lights nod as an audience, the scene soft with the gentle tom-tom of rain.

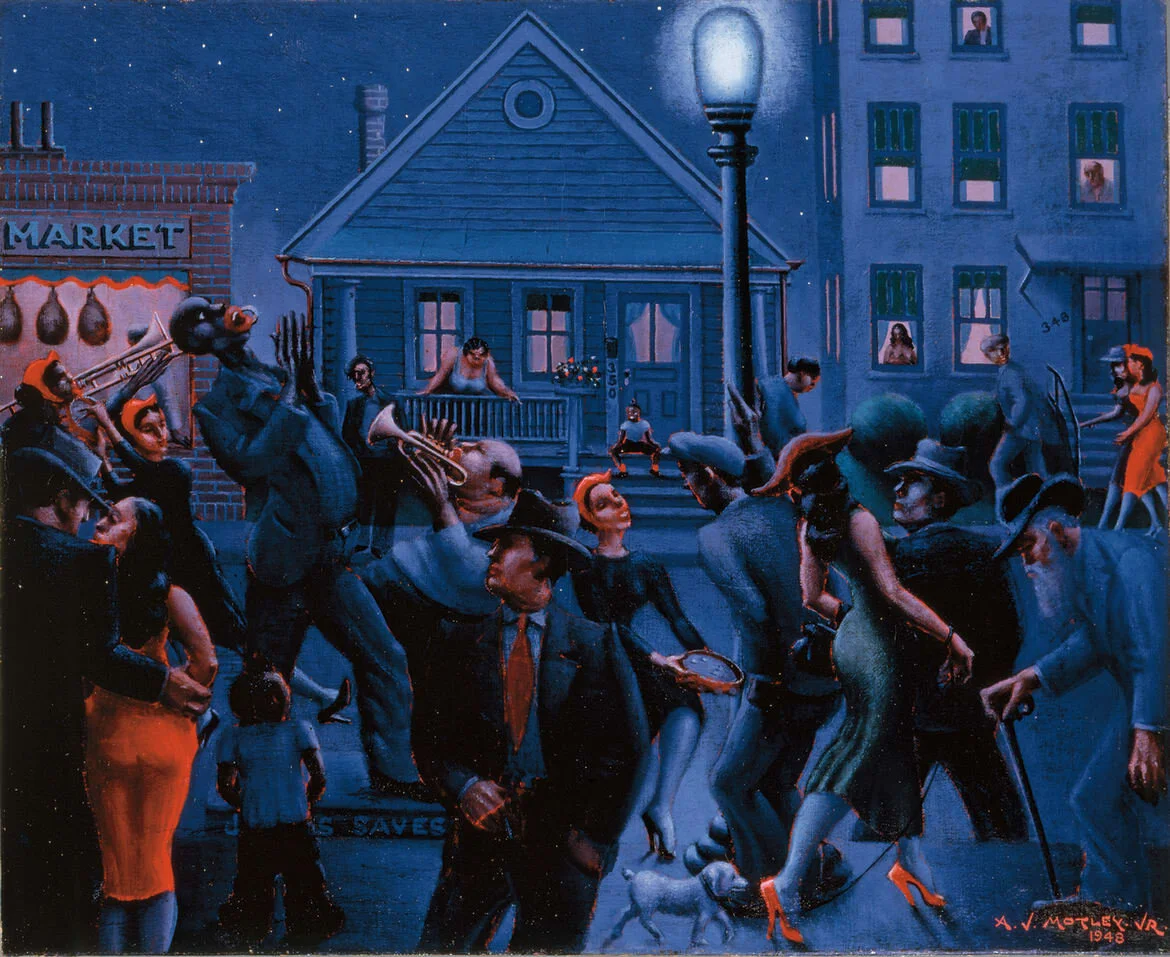

Painting by Archibald Motley, "Gettin' Religion"

References

[1] Armstrong, Louis and Fitzgerald, Ella. “Tenderly”. Edwin H. Morris & Company, Inc,

[2] Raboteau, Emily. “A Slip Into the Breaks: Teaching Jazz Poetry”. Teachers and Writers Magazine, 16 November 2016, Web.

[3] Raboteau, Emily. “A Slip Into the Breaks: Teaching Jazz Poetry”. Teachers and Writers Magazine, 16 November 2016, Web.

[4] Konc, Riane. “Jazz: A Few Definitions”. The New Yorker, 2 March 2017. Web.

[5] “A Brief Guide to Jazz Poetry”. poets.org, 17 May 2004. Web.

[6] “Kenneth Rexroth: Poetry Wedded to Jazz”. poets.org, 11 October 2004. Web.

[7] “Kenneth Rexroth: Poetry Wedded to Jazz”. poets.org, 11 October 2004. Web.

[8] “Kenneth Rexroth: Poetry Wedded to Jazz”. poets.org, 11 October 2004. Web.

[9] “Kenneth Rexroth: Poetry Wedded to Jazz”. poets.org, 11 October 2004. Web.

[10] Armstrong, Louis. “(What Did I Do To Be So) Black and Blue”. Matrix, 22 July 1929. Audio.

[11] Raboteau, Emily. “A Slip Into the Breaks: Teaching Jazz Poetry”. Teachers and Writers Magazine, 16 November 2016, Web.

[12] Konc, Riane. “Jazz: A Few Definitions”. The New Yorker, 2 March 2017. Web.

[13] Singer, Sean. “Scrapple from the Apple: Jazz & Poetry”. poets.org, 21 February 2014. Web.[14] Hughes, Langston and the Doug Parker Band. “The Weary Blues”. The 7 o’clock Show, 1958. Video.

[15] Singer, Sean. “Scrapple from the Apple: Jazz & Poetry”. poets.org, 21 February 2014. Web.[16] Perspectives Through Poetry: The Life & Legacy of Langston Hughes”. Web.

[17] Gross, Rebecca. “Jazz Poetry & Langston Hughes”. Art Works Blog, 11 April 2014. Web

[18] Gross, Rebecca. “Jazz Poetry & Langston Hughes”. Art Works Blog, 11 April 2014. Web

[19] Raboteau, Emily. “A Slip Into the Breaks: Teaching Jazz Poetry”. Teachers and Writers Magazine, 16 November 2016, Web.

[20] Raboteau, Emily. “A Slip Into the Breaks: Teaching Jazz Poetry”. Teachers and Writers Magazine, 16 November 2016, Web.

[21] Gross, Rebecca. “Jazz Poetry & Langston Hughes”. Art Works Blog, 11 April 2014. Web.

[22] Gross, Rebecca. “Jazz Poetry & Langston Hughes”. Art Works Blog, 11 April 2014. Web.

[23] Hughes, Langston. “Harlem”. Selected Poems of Langston Hughes, Random House Inc., 1990. Print.

[24] DeBello, Hadley. “Return to Harlem: The Modern Black Renaissance”. Harvard Political Review, 7 May 2017. Web.

[25] DeBello, Hadley. “Return to Harlem: The Modern Black Renaissance”. Harvard Political Review, 7 May 2017. Web.

[26] Daneman, Matthew. “Harlem renaissance ushered in new era of black pride”. USA Today, 3 February 2015. Web.

[27] Metcalfe, Josephine and Turner, Will. “Why rap should share a stage with poetry and jazz”. The Conversation, 23 November 2015. Web.

[28] Hughes, Langston. “Jazz as Communication”. Poetry Foundation, 13 October 2009. Web.[29] Konc, Riane. “Jazz: A Few Definitions”. The New Yorker, 2 March 2017. Web

[30] Camp, Lauren. “What’s in the Notes: The Sound of Jazz in Poetry”. World Literature Today, March 2011. Web.

[31] Camp, Lauren. “What’s in the Notes: The Sound of Jazz in Poetry”. World Literature Today, March 2011. Web.

[32] Raboteau, Emily. “A Slip Into the Breaks: Teaching Jazz Poetry”. Teachers and Writers Magazine, 16 November 2016, Web.

[33] Raboteau, Emily. “A Slip Into the Breaks: Teaching Jazz Poetry”. Teachers and Writers Magazine, 16 November 2016, Web.

[34] Camp, Lauren. “What’s in the Notes: The Sound of Jazz in Poetry”. World Literature Today, March 2011. Web.

[35] Camp, Lauren. “What’s in the Notes: The Sound of Jazz in Poetry”. World Literature Today, March 2011. Web.

[36] Konc, Riane. “Jazz: A Few Definitions”. The New Yorker, 2 March 2017. Web

[37] Singer, Sean. “Scrapple from the Apple: Jazz & Poetry”. poets.org, 21 February 2014. Web.[38] Baekgaard, Jakob. “The Word Is Beat: Jazz, Poetry & The Beat Generation”. all about jazz, 12 August 2015

[39] Baekgaard, Jakob. “The Word Is Beat: Jazz, Poetry & The Beat Generation”. all about jazz, 12 August 2015

[40] Baekgaard, Jakob. “The Word Is Beat: Jazz, Poetry & The Beat Generation”. all about jazz, 12 August 2015

[41] Baekgaard, Jakob. “The Word Is Beat: Jazz, Poetry & The Beat Generation”. all about jazz, 12 August 2015

[42] Baekgaard, Jakob. “The Word Is Beat: Jazz, Poetry & The Beat Generation”. all about jazz, 12 August 2015

[43] Hughes, Langston. “Jazz as Communication”. Poetry Foundation, 13 October 2009. Web.[44] Powers, Seth and Grenko, Maggie and Birks, Bryan and Lyon, Erika. “Perspectives Through Poetry: The Life & Legacy of Langston Hughes”. Web.

[45] Powers, Seth and Grenko, Maggie and Birks, Bryan and Lyon, Erika. “Perspectives Through Poetry: The Life & Legacy of Langston Hughes”. Web.

[46] Hughes, Langston. “Jazz as Communication”. Poetry Foundation, 13 October 2009. Web.[47] Singer, Sean. “Scrapple from the Apple: Jazz & Poetry”. poets.org, 21 February 2014. Web.[48] Gao, Baoyuan. “Jazz, Poetry, Rap: Cause and Effect of the Black Arts Movement”. Revive Music. Web.

[49] Gao, Baoyuan. “Jazz, Poetry, Rap: Cause and Effect of the Black Arts Movement”. Revive Music. Web.

[50] “The Langston Hughes Blog”. Web.

[51] Offendum, Omar. “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”. Youtube. Video.

[52] Offendum, Omar. “The Arab Speaks of Rivers”. Youtube. Video.

[53] “The Langston Hughes Blog”. Web.

[54] Konc, Riane. “Jazz: A Few Definitions”. The New Yorker, 2 March 2017. Web.